Just after ringing in the new year, Phillips opened the doors of its Park Avenue headquarters to New Landsa selling exhibition of work by about 65 contemporary Indigenous artists from the United States and Canada spanning seven decades.

The show (which closed on January 23) and the enthusiastic response from collectors are the latest signs that the market is finally catching up with the recent surge in curatorial interest. Jeffrey Gibson, a Cherokee-descended member of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, will be the first indigenous artist to represent the United States with a solo exhibition at this year’s Venice Biennale.

In 2023, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York staged, with excitement, the largest survey of the work of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, an 83-year-old citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation. Last September’s Armory Show included a special section curated by Candice Hopkins, an independent curator from Carcross/Tagish First Nation, featuring large-scale installations by Indigenous artists from across the Americas.

“It’s extraordinary what’s happening, this tide,” says James Trotta-Bono, a California-based trader who co-curated New Lands. “The institutions were very aware that the American art canon was fragmented at best in terms of its narrative, and they have been making a very concerted effort to increase exposure and awareness of Native American artists, both historical and contemporary.”

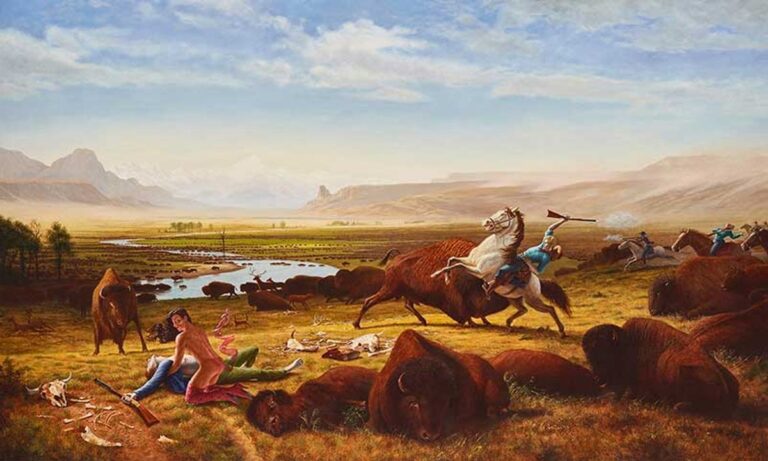

Trotta-Bono co-curated the exhibit with Bruce Hartman, the executive director and chief curator of the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art in Overland Park, Kansas, and Tony Abeyta, a Diné (Navajo) artist from New Mexico whose work was included in the exhibit. show, along with that of his father, Narciso Abeyta. Joining the Abeytas was an increasingly in-demand lineup with Gibson, Quick-to-See Smith, Oscar Howe, Kent Monkman, Marie Watt and Teresa Baker.

Phillips chose to offer the works through its private sales department, in part because few of the artists have public auction results, so it’s not optimal to introduce them to the broader market under the hammer, says Scott Nussbaum, Phillips vice president and specialist international senior of twentieth century and contemporary art. A private sale exhibition also allowed the pieces to remain in Phillips’ galleries in New York for much longer than the house would normally display auction lots.

“We wanted the show to have a little more longevity and give people a chance to come in and see it without a sense of rushed urgency,” says Nussbaum.

Active US and European buyers

The timing of the exhibition was also significant. January is traditionally the main month for American art in New York, with major auction houses selling stately portraits of the United States’ founding fathers, pastoral landscapes and domestic interiors, almost all by white artists. New Lands aims to expand the canon of American art to encompass contemporary indigenous artists.

Nussbaum says he’s never seen a sell-out show attract more institutional interest in his more than two decades in the business. While a spokesman for the house said it was too soon to share specific locations, he said collectors in both the United States and Europe had acquired pieces from the exhibition.

Trotta-Bono thinks one of the reasons the trade in recent Native American and Canadian First Nations art has been “exploding” in recent years is the amplification of the Black Lives Matter movement’s focus on all people of color working as artists .

“In terms of contemporary art, marginalized artists now have a stronger voice than ever before, and I think it was only a matter of time,” he says. “Indigenous artists are out there, creating compelling artwork. Their voices have been diminished for historical and racial reasons. And today’s sociopolitical landscape is ready and excited to stand up for the voices that have been stifled.”

“These artists talk about the most current issues, and that’s what contemporary art is all about. I think Native American artists are the vanguard of America.”