Among the surprises in the Van Gogh Museum collection is a group of brothel sketches by Emile Bernard, a young colleague of the Dutch artist. These drawings and watercolors provide an unusual insight into what today might seem like a curious choice of subject matter.

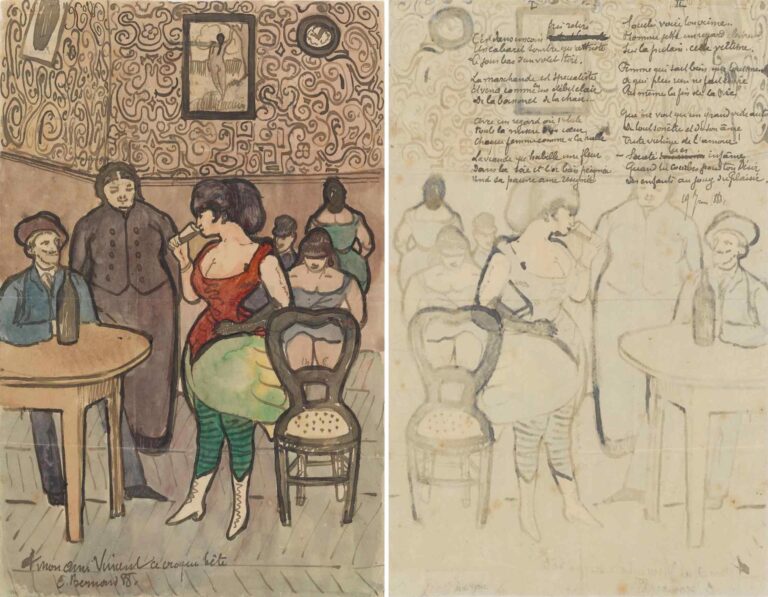

by Emile Bernard Brothel scene and poem on reverse (June 1888)

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

The two artists became friends in Paris in 1886 and after Van Gogh left for Arles in February 1888 they corresponded regularly and exchanged works of art. Of the 27 drawings that Bernard published in Van Gogh, 17 present prostitution (and two others are sexual allegories). Most have only been exhibited or reproduced occasionally.

These “scenes of brothels” are already properly cataloged, with the work carried out by Van Gogh Museum researcher Joost van der Hoeven. His detailed publication, which is online this week, explores these intriguing works.

What drew the two artists to this delicate subject? Van der Hoeven believes that it was not lasciviousness, but because prostitution represented “a modern subject”. That is, both artists and women who sold sex could be seen as challenging the bourgeois norms and values of society.

Van der Hoeven notes that Van Gogh and Bernard “saw marginalized women who participated in prostitution as people that avant-garde painters should support.” In this respect, he points out parallels with the way Van Gogh had painted the peasants of Brabant three years earlier.

Among the first works that Bernard published Van Gogh in Arles was Brothel sceneshipped June 1888. Aft lady watch as a younger woman pours a glass and seduces a customer in the salon. On the wall behind them hangs a painting of Eve: she reaches a branch to pluck the apple, just before the “fall.” Van Gogh replied that he found this watercolor “VERY VERY INTERESTING”, underlining his words in capital letters.

Bernard had inscribed the watercolor with an apparently casual comment in French, which translates as “For my friend Vincent, this silly sketch.” What’s on the reverse is a surprise: a poem Bernard had written about the evils of prostitution, condemning it as a depraved system that victimizes women.

It is difficult to reconcile the apparent contradiction between the image with its cheerful inscription and the sober poem. Perhaps they represent the confusion in the mind of young Bernard, who had just turned 20 years old.

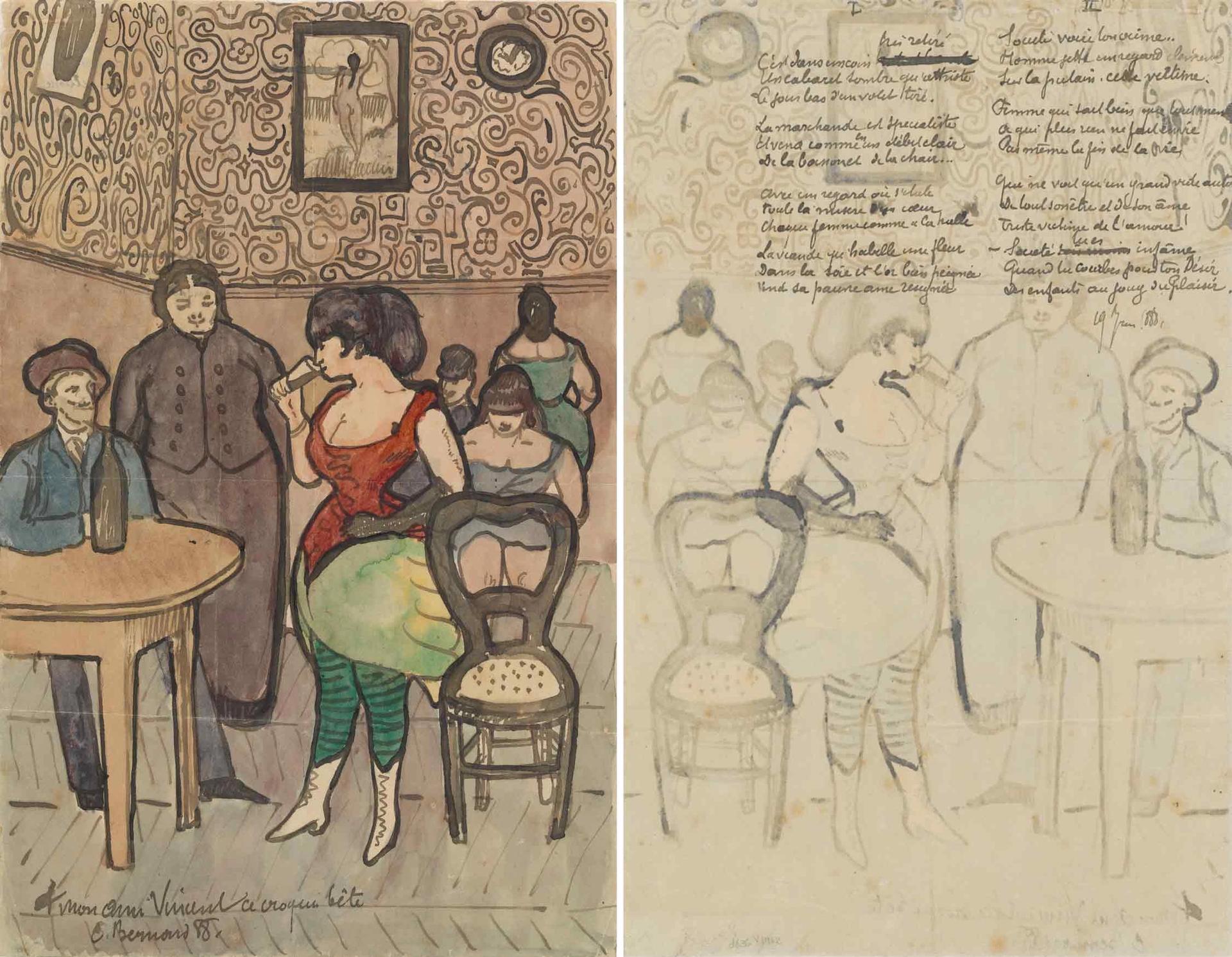

by Emile Bernard Female nude lying on a bed (July 1888)

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Bernard’s second batch of ten drawings, sent a month later, included Female nude lying on a bed. Although Bernard ordered his friend not to show these drawings to anyone, Vincent immediately sent them to his brother Theo in Paris: “He [Bernard] I am expressly forbidden to send them, but you will receive them by the same mail.” Vincent again approved of Bernard’s efforts, giving the works the award of being “very Rembrandtesque” and reminiscent of Francisco Goya.

Interestingly, the next brothel works were drawn on a folded piece of stationery from Au Printemps, the Parisian department store (which still exists). Conservatives recently discovered the store’s watermark on the paper.

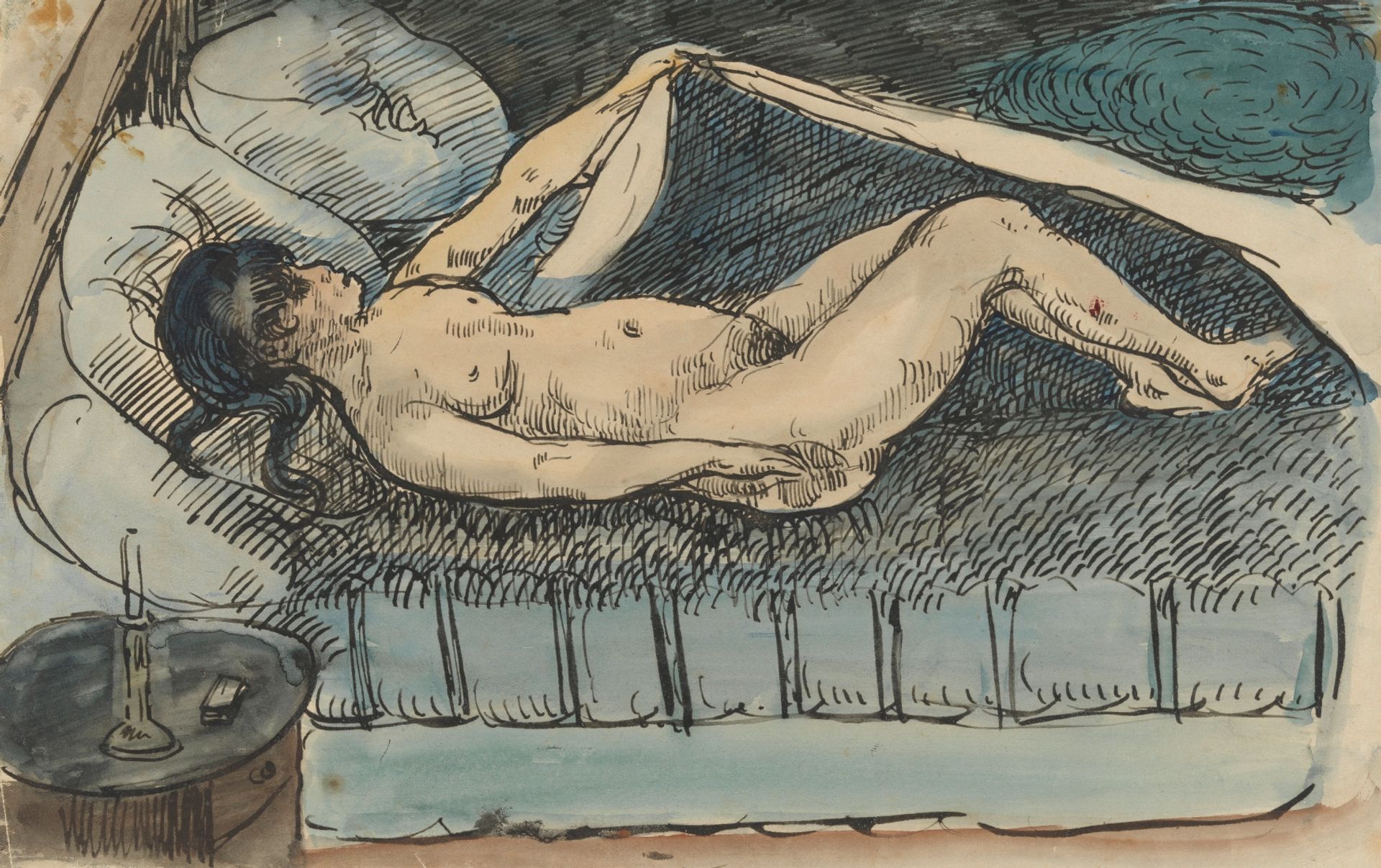

Bernard’s final drawings are a set of eleven submitted in October. These included a work he subtitled (in French) No one can pull a man’s strings as well as I canwhich seems to show the same model as in its predecessor Brothel scene.

by Emile Bernard No one can pull a man’s strings as well as I can (October 1888)

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Although Van Gogh expressed admiration for No one can pull a man’s strings as well as I can and another drawing, he was critical of the remaining nine. He complained to Bernard that they were “too vague, too little flesh and blood.”

Presumably Bernard knew the brothels in Montmartre, but what about the ones Van Gogh might have frequented in Arles? Van der Hoeven’s catalog focuses on Bernard’s drawings and attitudes, but what do Van Gogh’s letters and artworks reveal?

The Yellow House it was less than a five minute walk from the red light district and I would have passed by it every time I entered the city. Van Gogh called the place “the street of kind girls”.

In March 1888, three weeks after Van Gogh’s arrival, there was a fight involving a small group of Italian and French soldiers in the district, resulting in two murders. A few days later Vincent wrote to Theo that he “took the opportunity to enter one of the brothels”, apparently out of curiosity, reporting that so far this had represented “the limit of my amorous exploits in front of the Arlésiennes”. But at the beginning of October, Van Gogh complained to Theo that “for at least three weeks I haven’t had enough [money] go get a screw for three francs”.

Van Gogh did not send Bernard sketches of brothels (instead, he sent beautiful copies of his best paintings). However, he made two paintings of brothels for himself. The first, made in early October 1888, does not survive: it is most likely lost or destroyed by the artist, who may have been unhappy with it.

Paul Gauguin arrived in Arles on October 23, to stay at Casa Amarela and collaborate artistically with the Dutch artist. A week later Van Gogh told Bernard: “We have made a few excursions to the brothels, and it is likely that eventually we will go there often to work.”

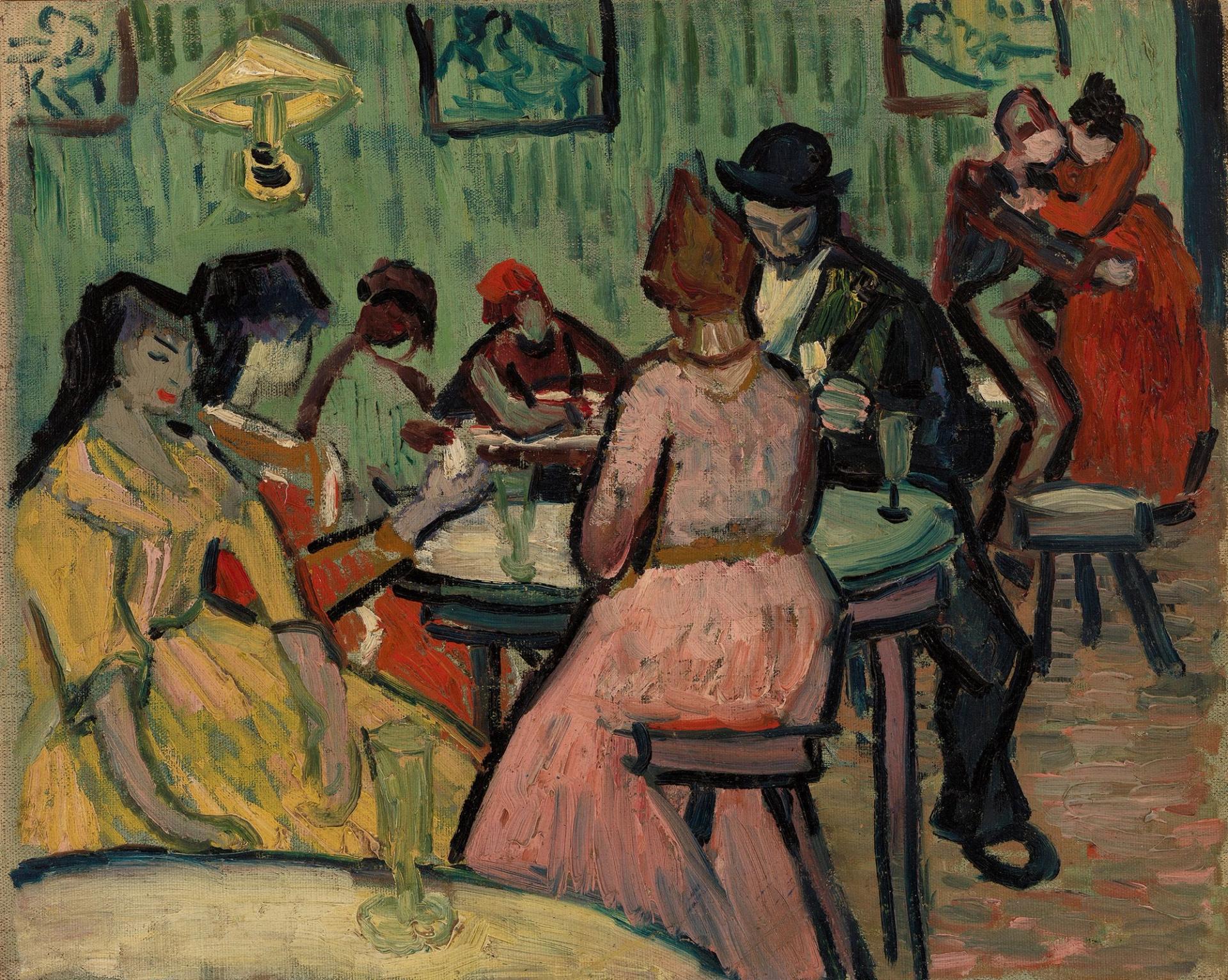

by Van Gogh O brothel (November 1888)

Barnes Collection, Philadelphia

Ten days later, Van Gogh informed Theo that “I have made a rough sketch of a brothel.” This should be it The brothel (November 1888), which is now in the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia.

Van Gogh depicted the salon. Three women in brightly colored dresses sit in the foreground. On the other side of the table a man in a dark hat holds a glass of absinthe. Further back are two soldiers, wearing red military caps and dancing or drinking with their comrades.

Following Bernard’s example, Van Gogh sketches three paintings hanging on the back wall. The one on the right reminds of Titian Venus of Urbino (1534, today Uffizi Galleries, Florence). Van Gogh’s painting is not an overtly sexual scene and without the artist’s title it could be mistaken for a slightly raucous late-night coffee.

artistically, The brothel It is hardly a success, mainly because Van Gogh liked to work in front of his subject, not from his imagination, as Bernard and Gauguin would. Van Gogh could hardly take his easel and paintings into a brothel and even surreptitious drawing would be very uncomfortable and risky. It was almost the hardest subject I could tackle.

Gauguin’s stay in Arles would come to a tragic end. Late on the night of December 23, 1888, in the Yellow House, Van Gogh mutilated his ear and wrapped the lump of cut meat in paper. He took the gruesome package to the brothel at 1 Rue de Bout d’Arles, handing it to a woman there.

Five weeks later, Van Gogh told Theo to return to the brothel “to see the girl I went to when I went crazy.” He admitted that she “suffered it and passed out but recovered her composure”, but “people say good things about her”.

The following month, Van Gogh complained that the neighbors were prying into his life when he was “in the middle of painting, eating or sleeping or fucking in the brothel (without a wife)”. This would be the last mention of the subject in Van Gogh’s correspondence.

Other Van Gogh news:

Cover by Nicholas Thomas Gauguin and Polynesiapublished by Head of Zeus/Bloomsbury, February

Many Van Gogh fans are also interested in Gauguin, and the latter is the subject of an important book published this month by Nicholas Thomas. Gauguin and Polynesia, as the title suggests, focuses on the artist’s life in Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands. What makes this publication particularly rewarding is that it is written by an anthropologist who did his first fieldwork in the Marquesas and who is a specialist in Pacific culture (and now director of the Cambridge Museum of Archeology and Anthropology). Thomas offers many new perspectives on Gauguin’s last years.