Art

Dodson jewelry

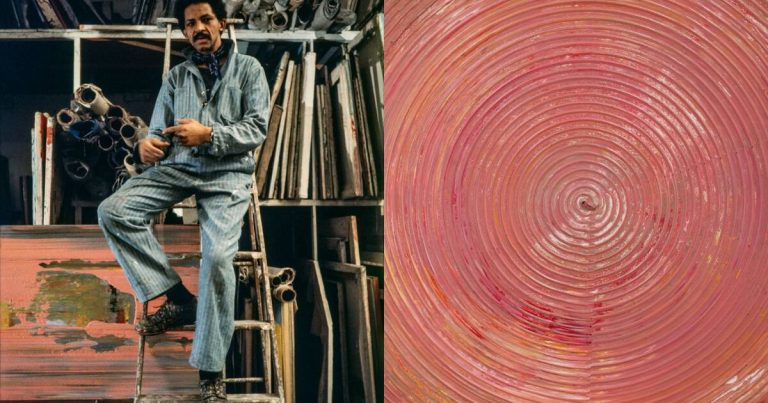

Portrait of Jack Whitten with Pink psyche queen (1973), Ca. 1975 © Jack Whitten Estate. Courtesy The Estate and Hauser & Wirth.

Jack Whitten. Siberian salt chopper . 1974. Photo by John Wronn. © 2025 The Museum of Modern Art, New York, courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

You can almost feel a Swoosh of Air as Cascada paint through the canvas in Jack Whitten First move (1974). In this abstract painting, Whitten’s eternal experimentation, something that was critical of his artistic practice, comes to life in a blow. The gentle smell, a photographic blur made with paint, shows the spectators the rhythm rhythm in which ideas, inspirations and innovations have been crossed.

This work, by the series promoted by Movement, “Lousa paintings”, appears in “Jack Whitten: The Messenger”, currently in view of the Museum of Modern Art. This retrospective examines 6 years of Whitten’s career through 175 paintings, sculptures and paper works that consider topics of race, war, awareness, technology, jazz and love.

Whitten was born in 1939 in Bessemer, Alabama and grew up in what he called “American Apartheid”. With stellar notes, he attended Tuskegee University with the intention of joining the military and becoming a doctor. But his call to create persisted and left Tuskegee to study art at South Baton Rouge University, Louisiana. There, at the Jim Crow -e South, Whitten’s political awareness was awakened. The vicesity of racism took him to the City of New York and in the fall of 1960 he began to study painting in the estimated Unión College Cooper. His colleagues included Norman Lewis, Romare Bearden and Jacob Lawrence; It was kind to the great Jazz Miles Davis and the Monk Thelonious, and kept a close contact with all -life influences Wiloning and Arshile Gorky.

Jack Whitten. NY BATTLE GROUND . 1967. Photo by Jonathan Muzikar. © 2025 The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

During this time, Whitten found that jazz was a trustworthy confident as he developed his practice. For him, the experimental nature of jazz was parallel to the intuition needed to create abstract art. In the late 1960s, he was deeply connected to the Zeitgeist, creating works of art that reflected the American experience. His piece New York Battle Terra (1967) is full of intense images, red explosions and orange explosions floating on a blue sky; Blood and death permeate the canvas. At that time, the Vietnam War had been on 13 years and was a turning point for breed issues in the United States. Many American blacks, who faced segregation and discrimination, have found it difficult to support the war. While they were fighting for basic rights as they sit in a lunch counter, they asked to risk their lives for the country itself that oppressed them.

When the Civil Rights Movement created a tectonic change in America, Whitten delved into abstract expressionism with vibrant, intense and emotional works. At this time, Whitten created a series, inspired by a 1957 match with Dr. King. Such a job, King Garden #4 (1968), it presents a rich mixture of plum purples, granza red, mustard yellow and olive green: an lush variety of colors and brushstrokes in conversation with each other. The painting captures a world that Dr. King dreamed of, a place where the color does not know limits.

8

See Slide Presentation

During the 1960s and 70s, there was an increase in black abstraction. Many artists found in abstract works in a new path that has not changed with the stories of racism, sexism and elitism. However, black artists such as Sam Gilliam, Ed Clark, Alma Thomas and Howarena Pindell often felt the double -phil of abstraction sword. They were not allowed in the elite spaces of Art because of their race (and in some cases, their genre). At the same time, black abstracts were accused of not contributing to the political agendas of black power, progress and revolution. Although the black figuration pushed directly against negative narratives about blacks, abstract works like Whitten have not been interpreted as clear statements of protest in the same way. For Whitten, however, abstraction offered a radical space of free imagination of the oppression of racism. For black abstract artists, reimagining your space and yourself as unlimited in the midst of systemic racism was (and is still) powerful.

Throughout the exhibition, it is clear that curiosity, experimentation and innovation were the fundamental principles of Whitten practice, which only increased over time. In Golden spaces (1971), whitten layers paint and used the sawmill of a mountain range to create undulating skyscrapers that reveal a colorful spectrum underneath. This technique caused the painting to lift the canvas, breaking the notion of paint deeply rooted as a flat and two -dimensional medium.

Another of your techniques was to use your Afro choice for combws through layers. Whitten has further revolutionized his process by inventing a tool called “developer”, a 40 -pound wooden site with a base 12 meters long. He threw layers of paint and swept the developer through the canvas, mixing the colors in a way that created an almost photographic meaning of movement. This manpower intensive technique has produced effects that the art world had never seen before. In Pink psyche queen (1973), the layers of green and gray look through a surface of bubble rose, with a triangle shape located subtly in the center. Whitten often used a carpenter blade to carve through thick layers of acrylic paint, introducing new methods of manufacturing brands in the middle.

Jack Whitten, detail of Four wheel. 1970 © Jack Whitten Estate. Photo by Genevieve Hanson. Courtesy The Estate and Hauser & Wirth,

As “The Messenger” shows, Whitten went on to new experiments with paint, moving away from a wet palette to work only in a dry one. In this process, he used “Tesserae”, the founding mosaic technique. Cape paint sometimes seven centimeters thick, let it dry and then cut it into small pieces. He lacked the paint cubes, which were transformed into luminous tiles. Whitten then applied the tiles to a dry canvas with a sticker. Whitten tried and tried several processes, such as freezing the paint cubes dry, sometimes spraying them ash and dust, which have joined the paintings again.

Whitten began his “Black Monolith” series in the late 1980s, and became one of the most intensive and extensive work bodies in his career. The series is a continuum of love letters to heroes and black icons. Many of the pieces were made in honor of specific individuals, such as Maya Angelou, Muhammad Ali, James Baldwin and Web du Bois, people who, like Whitten, were prolific and left lasting impacts on black culture and society as a whole. The series reached a new peak with Black Monolith III for Barbara Jordan (1998). Jordan, lawyer and teacher, was the first black woman in the south chosen to Congress. In this piece, Whitten has developed another innovation, raising the canvas of the canvas, creating a brilliant mountain of peaks and valleys that reflect the iconic life of Barbara Jordan.

Jazz continued to inspire Whitten. In his practice, he made tributes to John Coltrane, Miles Davis, and even named The messenger (for art blakey) (1990), after the beloved jazz drummer who inspired him. Whitten thickened the paint, cut it into small black tiles and applied it on the canvas. Then he splared the white paint on the tiles. The result is a series of supernovas that broke out in Stardust. Moving for the freedom of jazz, Whitten’s work suggests a savage cosmos, where everything is possible.

Jack Whitten. ATÓPOLIS: For the sliding of Édouard . 2014. Photo by Jonathan Muzikar. © 2025 The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

ATÓPOLIS: For the sliding of Édouard (2014), It is the crescendo of the exhibition. It is Whitten’s greatest work, which covers eight panels, a behemoth master who uses the TestSerae technique to build a intricate and brilliant map. Whitten refers to the theory of the philosopher of Martiniquais, Édouard Glissant of “Acópolis”, a powerful concept for the people of the African diaspora, whose identity is usually linked to the meaning of the place. This work, made from thousands of acrylic tiles and spreads, embedded with a series of anthracite aluminum media, creates a constellation of ways that imagines a new sense of place for black identity. Whitten Atopolis It represents a utopia composed of numerous elements, a city born of the displaced, not anchored and nomadic experiences of the descendants of the Transatlantic Slave trade. A place where all relationships are “completely interconnected and egalitarian,” Whitten said. Work is an act of love, offering viewers who have not yet found their place in the world a model to create a sense of belonging and home for themselves.

Whitten’s work, always intensive at work and driven by innovation, has rightly won a place in the pantheon of greater abstractions, as shown “Jack Whitten: The Messenger”. The artist’s relentless passion and unlimited curiosity fueled his brave experimentation, allowing him to do what all great artists do.