Deborah K. Tash was born in 1949 and grew up in California’s Bay Area, where art and language found their way into her life early. She calls herself a Mestiza, a woman rooted in both Mexican and Celtic traditions—her mother’s Indigenous Mexican ancestry and her father’s Celtic bloodline flow together in her work. That duality is not a theme; it’s the essence. For Tash, art isn’t about choosing between story and sculpture, land or spirit—it’s about blending them, letting them speak all at once. Her life’s work has been about that union: poetry and visual art, ancestry and emotion, the sacred and the wounded. Nothing stands alone.

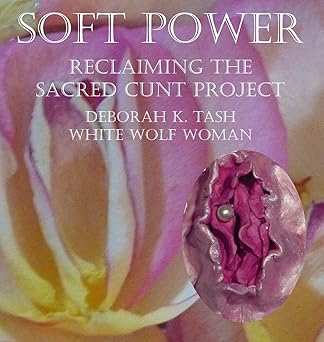

Her series, Soft Power, and the project it anchors—Reclaiming The Sacred Cunt—bring that philosophy into form. It’s visual storytelling, spiritual reclamation, and personal healing all rolled into ceramic, symbolism, and shape.

Let’s talk about one of her works in particular.

Cunt Egg XXII Tonantzin-Guadalupe is part of the Soft Power Series and now lives in the collection of herchurch San Francisco, a progressive Lutheran church known for honoring the sacred feminine. The piece is a ceramic sculpture, abstract and visceral. It doesn’t ask permission. It sits firmly in its own power—a cunt-shaped egg form resting in a wave, floating on a crescent moon, surrounded by metal stars. Its base is lined with roses, eggs, green snakes, and golden orbs. Every detail is there for a reason.

The work is a dedication to Tonantzin, the Aztec earth mother, who centuries later morphed into the Virgin of Guadalupe. That overlap—Indigenous goddess and Catholic saint—isn’t just myth or history. For Tash, it’s personal. It’s the wound of colonization and the act of remembering what came before. This sculpture doesn’t try to reconcile them. Instead, it holds both. It lets them coexist.

Cunt Egg XXII isn’t soft in the conventional sense. It’s tender in its openness, but fierce in its refusal to hide. The snakes and orbs carry symbolic weight—creation, rebirth, temptation, transformation. The roses? Love and beauty, yes, but also pain. The egg itself is life-giving and vulnerable. And the cunt—reclaimed, sacred, centered—becomes a vessel, a shrine, a statement.

This is what Tash means by “soft power.” It’s not weakness. It’s the kind of strength that comes from healing, from being brave enough to tell the story no one wants to hear. The kind of power that doesn’t rely on dominance or shame. She uses the female body—not as an object—but as a doorway into memory, trauma, and spiritual force. It’s about holding space for pain and honoring survival.

The Soft Power Series is deeply tied to her book, also titled Soft Power, which gathers her visual work alongside poetry and personal narrative. The book, like the sculpture, explores sexual trauma and healing through a shamanic lens. It’s erotic, grounded, and unflinching. She doesn’t separate the sensual from the spiritual—instead, she shows how one helps reclaim the other. Art becomes a healing act. Poetry becomes medicine.

Tash isn’t trying to shock anyone. She’s trying to wake something up. Something ancient. Something that knows the body remembers. That the earth is sacred. That sexuality can be holy. In a world that often splits these things apart, she insists they belong together.

And it’s not just her personal story she’s telling. Her work opens a space for other women—for anyone, really—who has felt silenced, shamed, or cut off from their own power. Reclaiming The Sacred Cunt is exactly what it sounds like: a refusal to keep hiding, a way back to the body as sacred space.

There’s nothing polished or commercial here. It’s raw, grounded in handmade clay and honest words. You don’t look at one of her sculptures and think “decorative.” You look at it and feel the pull of something deeper. The piece sits there, almost like an altar, and invites you to listen.

Deborah K. Tash isn’t just an artist. She’s a storyteller, a spiritual worker, and a bridge between worlds. Her hands shape clay, but they’re also shaping memory, myth, and the possibility of healing. Through her work, she invites people to remember what’s been forgotten—or forced into hiding—and to hold it with reverence.