Haeley Kyong makes work that doesn’t ask you to “get it.” It asks you to feel it.

Her practice is rooted in the idea that art can reach people before language does—before explanations, before categories, before the brain starts sorting everything into neat boxes. Kyong isn’t trying to build puzzles. She’s trying to build contact. The kind that hits you in the chest first, and only later becomes something you can describe.

Born and raised in South Korea, Kyong carries that early sense of place with her, but she’s also shaped by years of living and studying in New York. She attended the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University, and later studied at Columbia University. That combination matters, not because of the names, but because it points to the dual tension that runs through her work: structure and openness. Discipline and intuition. The learned parts of making, and the part that can’t be taught—attention, restraint, timing.

Her visual language is minimalist, but it’s not minimal in emotional range. A lot of people hear “minimal” and think “cold.” Kyong’s work pushes against that assumption. She pares back the clutter so the emotional signal can come through without interference. She removes the extra so the essential can hold the space.

When you stand in front of a Kyong piece, you’re not being flooded with imagery or narrative. Instead, you’re being given a few precise elements—shape, color, spacing, rhythm—and asked to meet them halfway. That meeting is where her work lives. It’s not a lecture. It’s an exchange.

Kyong often builds compositions around fundamental forms and clear color relationships. She’s interested in how small shifts—one hue tipping warmer, one edge softening, one interval widening—can change the entire temperature of a piece. In that way, her work operates like music: a limited set of notes, arranged in a way that lands differently depending on how you’re listening, and what you’re carrying with you that day.

This is where her philosophy comes into focus. Kyong aims to bypass the part of us that overthinks. The work doesn’t rely on cleverness. It relies on recognition—something bodily, instinctive, immediate. You might not know why a certain arrangement makes you feel calm, or tense, or suddenly alert, but you feel it anyway. And that reaction becomes part of the artwork’s content.

One piece that captures this approach is Color Wave. It reads, at first glance, as a mosaic: individual tiles, each carrying its own palette. The viewer can register the whole image quickly, but the real pull is in the differences. Every tile has its own identity, its own mood, its own internal logic. Some feel bright and open. Others feel muted, even private. Yet they sit together, edge-to-edge, as a unified field.

Color Wave becomes an elegant metaphor without turning into a slogan. The tiles are separate, but they don’t compete. They don’t cancel one another out. They create a larger rhythm through contrast. It’s easy to see this as a reflection of human life: distinct perspectives, distinct histories, distinct emotional registers—held together in one shared world. The piece doesn’t force a moral. It simply shows how variety can be coherent without becoming uniform.

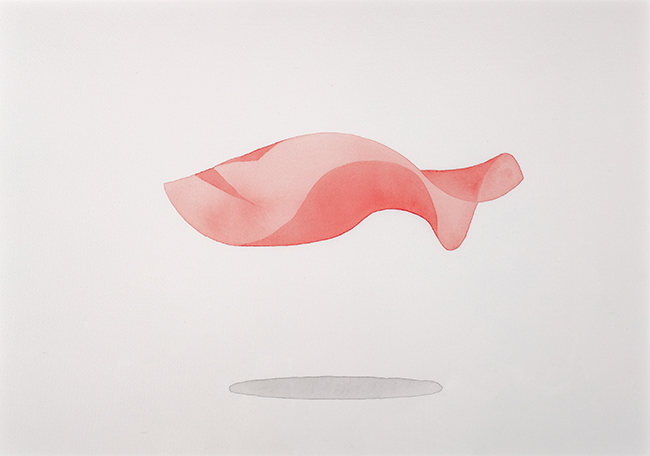

If Color Wave is about difference held in unity, Kyong’s watercolor series Undulation is about movement—internal, shifting, hard to pin down. The series consists of five paintings centered on a flat square that seems to lift and travel through space. The shape stays simple, but its motion is surprisingly expressive. It bends, dips, rises, and changes posture the way a body does when it’s thinking, hesitating, deciding, letting go.

Kyong has described the series as being inspired by the flight of a bird, and you can sense that influence in the way the form seems to catch air. But the work isn’t about birds in any literal sense. It’s about the feeling of wanting freedom, and the fact that freedom often arrives tangled with fear. That’s the emotional engine of the series: the lift and the wobble. The desire to move forward, and the inner pullback that comes with it.

In each painting, the square takes on a slightly different state—almost like frames in a short sequence. The colors remain delicate, the edges often softened by watercolor’s natural drift. That softness is important. It keeps the work from feeling mechanical. Even though the central form is geometric, the medium introduces breath: bloom, bleed, transparency, the trace of a hand working with water rather than against it.

The result is strangely intimate. You’re watching a simple form behave like a feeling.

What makes Kyong’s work compelling is not complexity of imagery, but clarity of intention. She trusts the viewer. She doesn’t rush to explain. Instead, she creates conditions where a viewer can arrive at something personal. Her minimal approach clears the stage so the person standing in front of the piece becomes part of what’s happening. The work is quiet, but it isn’t passive. It asks for presence.

This is also where her education plays a subtle role. Training can sometimes lead artists to overbuild—to prove skill, to show range, to pack meaning into every corner. Kyong moves the other way. She uses her foundation to refine rather than decorate. The work feels considered, but not overworked. There’s room for the viewer’s mind to move, and room for emotion to rise without being told what it should be.

At its core, Kyong’s practice is about introspection. Not as a trendy buzzword, but as a real event: that moment when you notice yourself noticing. A Kyong piece can act like a pause button. It slows the internal noise long enough for something honest to surface.

And maybe that’s the point. Her work suggests that we don’t always need more information. Sometimes we need less—less clutter, less performance, less speed—so we can actually feel what’s already there.

Haeley Kyong creates art that is distilled, direct, and deeply human. With a small set of tools—shape, color, rhythm—she opens a wide emotional field. Her pieces don’t demand attention with volume. They hold attention with focus. And in that focus, they offer something rare: a clean space where a person can reflect, reset, and recognize themselves.