Born in 1965 in Montreal, Doug Caplan’s relationship with photography started with a simple Polaroid. He was a teenager when his parents handed him the camera—plastic, manual, and unforgettable mostly for the smell of developing film. That moment didn’t ignite an instant obsession, but it planted something. Life carried on. It wasn’t until the early 1990s, after settling into married life, that photography returned with more weight and purpose. This time, it stuck.

Over the years, Caplan has worked with both film and digital formats, but what stands out is his eye—not for drama, but for things we’re trained to ignore. His images don’t chase spectacle. They catch the hum of a city’s backbeat. His focus lands on what the world usually leaves behind, revealing quiet compositions tucked inside function, clutter, or urban routine.

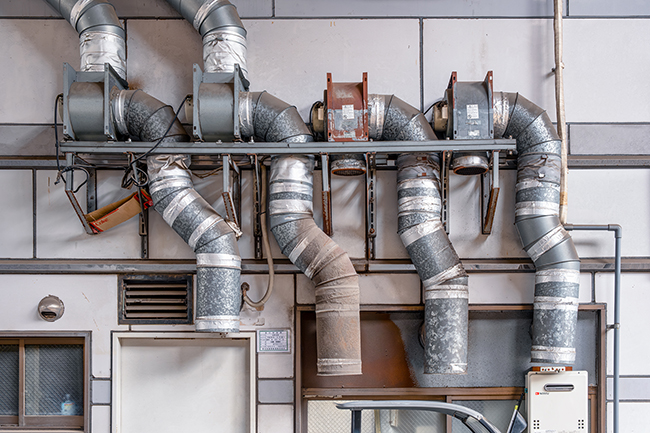

Ductwork Ballet

In Ductwork Ballet, Caplan brings attention to a web of industrial tubing lining a building wall in Tokyo. There’s no hero, no action—just metal pipes winding in all directions. But under his lens, those ducts move. Not literally, but visually. Each bend, twist, and intersection feels deliberate, like the pause and stretch of a dancer mid-performance.

This isn’t beauty in the traditional sense. It’s practical design—unapologetically so. But Caplan frames it to show something more: unintentional harmony. Pipes meant to move air suddenly resemble a score of improvised movement. The result is almost musical. The photo doesn’t elevate the ducts so much as let them speak for themselves.

Snakes & Ladders

Shot elsewhere in Tokyo, Snakes & Ladders keeps with the same thread—utility as subject. This time, wires, vents, and ladders make up the frame. They don’t organize neatly. They weave, dangle, stack. It’s a photo full of quiet tension. And in the middle of it, a single yellow window glows, hinting at life somewhere behind all the steel and concrete.

The name calls up a childhood board game, but the mood here is reflective, not playful. The image shows a hidden part of the city’s inner mechanics—the stuff that powers daily life, mostly ignored until it breaks. Caplan seems to ask: What if we looked at these in-between spaces the same way we admire a skyline?

The beauty here isn’t polished or obvious. It’s buried in how things connect—or barely do. It’s about structure and mess coexisting. And it’s this exact balance that makes Caplan’s work feel honest.

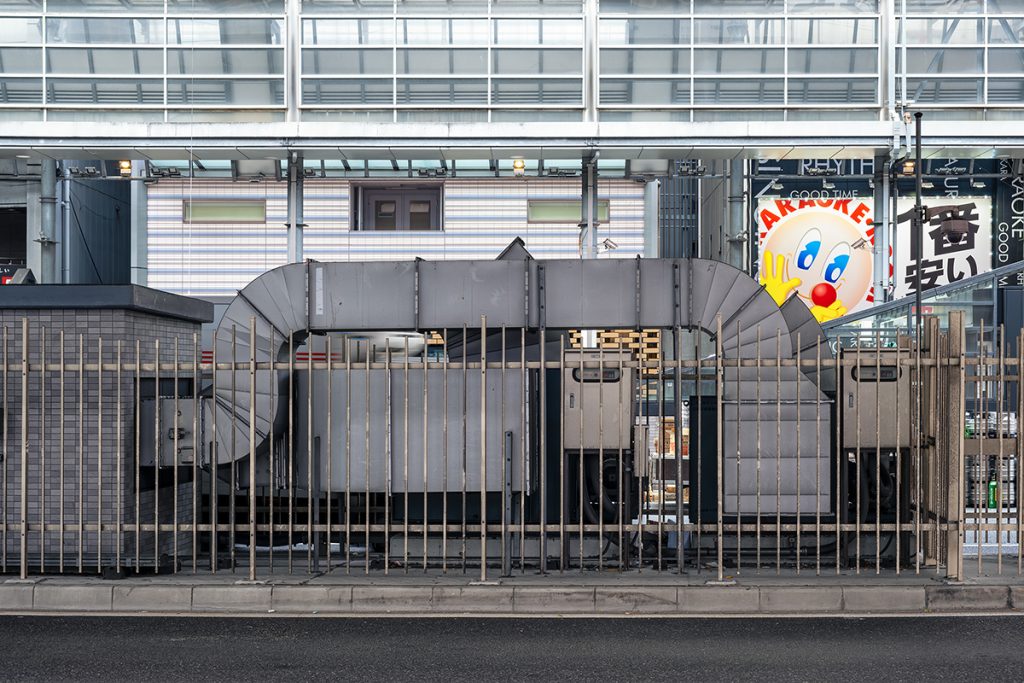

The Absurdity of Existence

In The Absurdity of Existence, taken in Osaka, Caplan moves into more surreal territory. At first glance, the image is all clean lines and neutral tones. You expect it to be orderly. Then comes the twist: a bright, cartoonish face—smiling, oversized, and out of place—sits square in the middle of the scene.

It’s unexpected. It’s silly. But it doesn’t feel wrong. Caplan doesn’t treat the face as a disruption. It becomes part of the system, a reminder that absurdity isn’t something that breaks into our lives. It’s built in. This photograph holds a kind of visual contradiction: planning meets randomness, control meets whimsy.

The message is clear, but subtle: cities aren’t only logical. They’re also strange, layered, and often a little funny when you stop to look. That tension is what Caplan captures best.

Doug Caplan doesn’t photograph the obvious. He looks for the poetry inside infrastructure, the character in clutter, the humor in the forgotten. His work doesn’t demand attention—it suggests it. Whether showing pipes tangled across a wall or a goofy face staring out from a grid of concrete, his images ask the same thing: look again. There’s more there than you thought.