Helena Kotnik approaches painting like a quiet excavation. With degrees in Fine Arts from Barcelona University and the Akademie der bildende Künste in Vienna, and a Master’s that sharpened her conceptual eye, she works from the inside out—digging into culture, psychology, and form. Her work straddles the border between reflection and critique. She doesn’t decorate; she investigates. Drawing from recognizable sources—classic paintings, social roles, personal moments—she reconfigures them, less as references than as tools for inquiry.

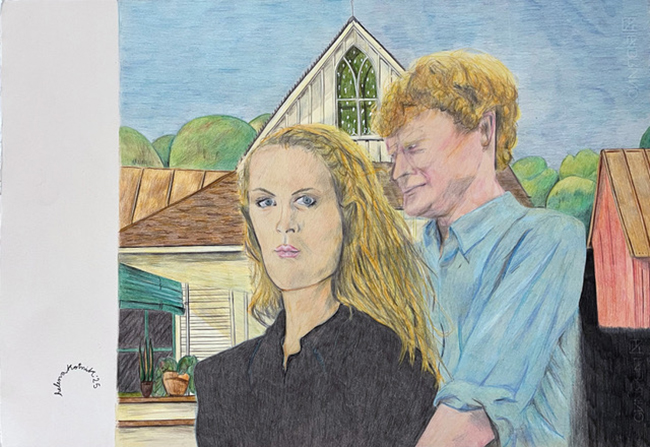

Take Friends (2025), a piece loosely anchored to Grant Wood’s American Gothic. Kotnik doesn’t copy or parody the original. Instead, she pulls it apart and reassembles the idea with new urgency. Her version replaces stoic farmers with contemporary women, unposed and calm, yet charged with presence. Painted in gouache and pencil colors, it measures 70 by 50 centimeters. The house is gone. What remains is the dynamic between the women and the silent implications of where they stand.

There’s no drama in the scene, but that’s where the tension builds. The stillness hums. In Kotnik’s hands, stillness doesn’t mean pause—it means build-up. Time is present in the painting, pushing against the surface. She’s asking what roles women have been given, and which ones they’ve taken for themselves. The nod to American Gothic isn’t nostalgia; it’s a reset.

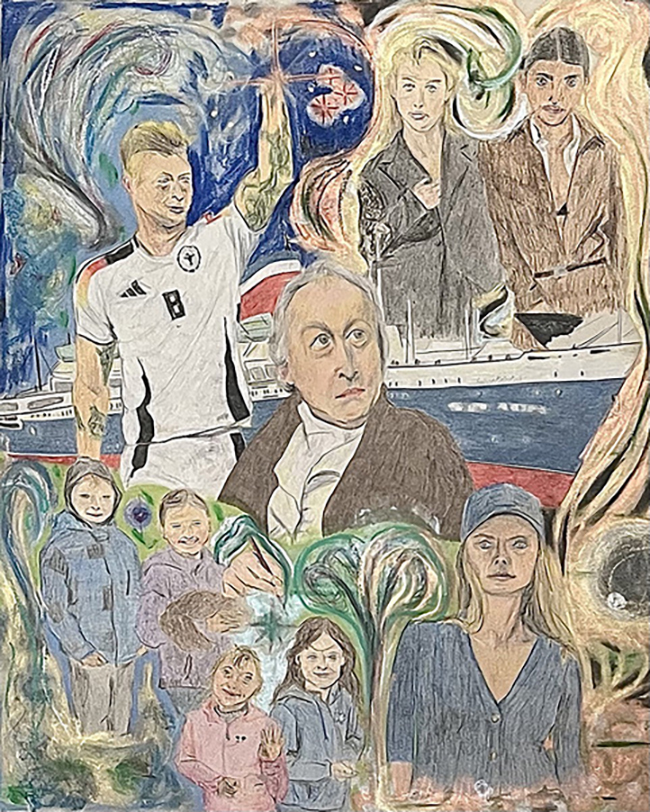

Her work Freedom (2025) offers a different tone. Created with pencil colors and soft pastel, it’s lighter both visually and emotionally. The 65 x 50 cm composition drifts gently but with purpose. It’s not an abstract piece, but it edges toward the atmospheric. The subject is a feeling—that moment when things fall into place, when you recognize yourself and your path at the same time. Kotnik paints that moment without pinning it down.

The sense of movement here isn’t external. It’s internal, slow, and reflective. There’s a suggestion of progress—not the linear kind, but layered, like memory or music. In Freedom, Kotnik brings attention to how events fold into each other, how alignment happens through connection. The piece feels light, but not shallow. It’s grounded in a deeper rhythm—one that tracks emotional flow and historic motion in equal measure.

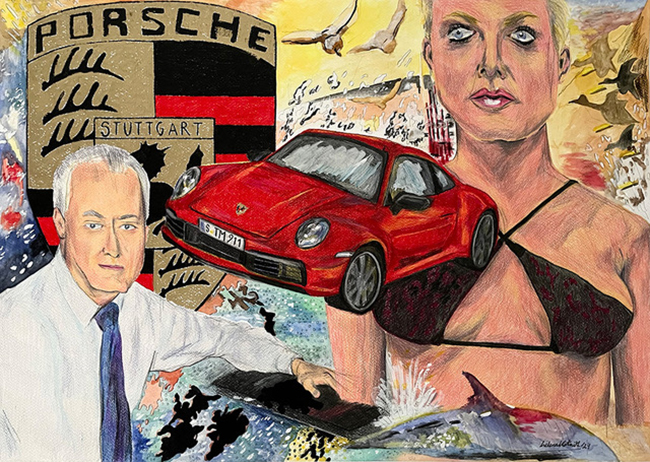

Then there’s Porsche (2024), where she shifts gears. This piece uses gouache, ink, pencil colors, soft pastel, and watercolor, combining materials the way some artists mix metaphors. Porsche may seem to be about a car, but it’s really about what the car stands for. Speed. Status. Control. Modernity as dream. Kotnik doesn’t mock these ideas, but she doesn’t celebrate them either. She captures them mid-transformation—caught between icon and illusion.

What’s interesting here is how carefully she composes the contradictions. There’s beauty in the lines, in the softness of the pastel and the gloss of gouache. But that beauty is carrying weight. She paints the myth, yes—but also the mechanism underneath it. The painting sits in that space between critique and curiosity, acknowledging that the world we shape is often built from contradictions we don’t bother to question.

These three paintings—Friends, Freedom, and Porsche—each move in their own direction, but together they form a kind of conversation. Kotnik works across themes of identity, structure, and belief. She asks how we position ourselves in a world full of symbols and shifting meanings. Her palette is subtle, her lines deliberate, but the impact lands with clarity.

She doesn’t wrap things up. Her paintings don’t answer the questions they raise. Instead, they leave room. Her work is a kind of thinking—a visual essay, slow and open-ended. In a world full of noise, Helena Kotnik offers something quieter and more persistent: a space to reflect, and a reason to look a little closer.