John Gardner’s journey into sculpture is as textured and layered as his bronzes. He is a storyteller with clay and metal, capturing more than just the physical likeness of his subjects. His sculptures radiate warmth and humanity—qualities he believes history should remember alongside the achievements of remarkable individuals. For Gardner, the work is not about chasing perfection, but about revealing essence. He sees his role as translating memory, spirit, and lived character into a physical form that endures. His bronzes are human in the truest sense—faces that carry emotion, postures that hold presence, gestures that remain long after the people themselves are gone.

The Work: Helen Suzman

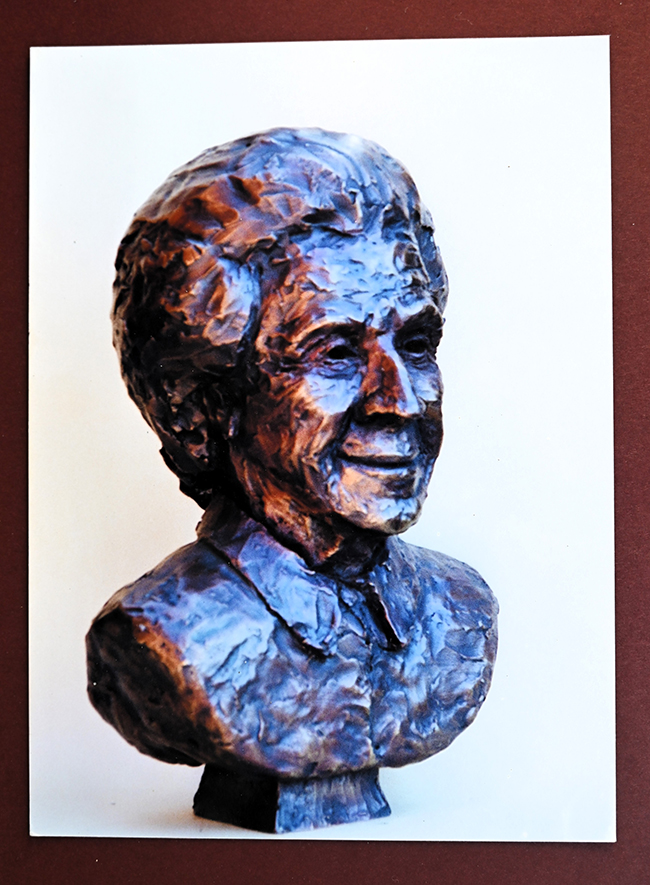

The bust of Helen Suzman, created by Gardner, is a study in empathy as much as it is in form. Suzman, a South African anti-apartheid activist and politician, spent decades as a lone parliamentary voice against racial segregation and injustice. To sculpt her likeness is to carry not only the weight of her public record but also the warmth of her humanity. Gardner approached the task with an eye for both strength and softness.

The sculpture captures Suzman mid-expression, a face alive with thought and energy. Her smile is gentle, almost understated, but carries an undeniable assurance. It is not the frozen smile of a posed figure—it feels lived-in, as though she has just finished making a sharp remark or is about to share a wry observation. Gardner’s decision to present her this way reflects his sense of who she was: firm, principled, but also approachable, witty, and deeply human.

The surface of the bronze is textured, not smoothed into sterile perfection. Gardner’s marks remain visible, giving the work vitality. Light catches on the ridges of her hair, across her forehead, and along the folds of her blouse. This roughness is not unfinished—it is intentional. It mirrors the turbulence of the world Suzman moved through, while also suggesting that human presence is never flat or polished. Real life carries edges, grooves, and irregularities, and Gardner allows that truth to stay alive in the metal.

Memory in Material

Bronze has long been a material associated with permanence. Leaders, thinkers, and cultural figures have often been immortalized in its weight and sheen. Yet Gardner’s Helen Suzman resists the stiff solemnity often found in traditional portrait busts. Instead of an icon locked in grandeur, Suzman here feels approachable. She is remembered not only for what she accomplished but for how she carried herself—her wit, her tenacity, her humanity.

The warmth of the bust lies in the small choices: the upward curve of her mouth, the slight lift of her eyes, the natural drape of her collar. These touches transform the sculpture from representation into presence. One feels not just that Suzman is being remembered, but that she is still here, meeting our gaze.

Between Likeness and Spirit

Gardner’s approach to portraiture straddles the line between capturing likeness and evoking spirit. With Suzman, he leaned into both. The physical resemblance is clear, but more importantly, the sculpture feels alive with her character. This reflects Gardner’s broader philosophy of what art should do: it should not simply preserve an image but should carry forward a person’s essence, making it available for future generations to encounter.

In Suzman’s case, this is especially meaningful. She stood for justice in a time and place where speaking out came at a cost. Her courage was lived daily, in isolation, as one of the very few white South Africans in parliament to challenge apartheid laws openly. Gardner’s sculpture does not show that directly—it doesn’t depict protest, struggle, or political strife. Instead, it shows the woman herself, the human being who bore the weight of those battles.

Conversation with History

Every portrait bust is, in some sense, a conversation with history. In Helen Suzman, Gardner chooses to converse not with a political record or a long list of speeches, but with the person who carried them. He chose not to monumentalize her into abstraction, but to bring her back to the level of encounter. Viewers can stand face to face with her, catch a trace of her humor, see the resilience etched into her skin, and remember that history is made not only by ideas but by people.

Closing Thoughts

Gardner’s Helen Suzman is more than bronze. It is a reminder of presence, of humanity remembered with care. In capturing her with both dignity and warmth, Gardner shows us that portraiture can resist the coldness of stone monuments and instead offer a more intimate form of remembrance. Suzman’s fight against apartheid was historic, but Gardner’s sculpture insists that her humanity be remembered alongside her courage. In that sense, it does exactly what Gardner sets out to do: it tells a story, layered and textured, that lives on in metal and memory.