Julian Jamaal Jones grew up in Indianapolis, Indiana, before he ever imagined becoming a multidisciplinary artist and educator. His path into the arts did not arrive through one transformative moment. Instead, it emerged slowly through lived culture, family memory, and an ongoing fascination with the images, symbols, and textures surrounding him as a child. Jones eventually built a practice that spans photography, quilting, performance, and historical research. These mediums serve different functions, yet they share a single foundation: using creativity to honor the stories carried through African American life.

For Jones, artmaking is not simply an attempt to invent something new. It is a response to history—listening to existing tradition rather than ignoring it. African American quilting, especially, informs his sense of identity and purpose. He is committed to reshaping this tradition on his own terms, refusing strict rules and transforming the quilt into a contemporary language that belongs to him. This desire to reinterpret textile history fuels every part of his artistic work.

Jones’s broader practice positions him within the current landscape of American art, yet his themes look backward and forward at once. His focus returns often to memory: fragmented stories, family photographs, cultural patterning, and inherited emotion. He approaches quilts as living carriers of history rather than decorative objects. The quilt becomes a way to preserve identity, a physical site where experience is stitched into shape. Jones works with vibrant color, intentional stitching, photography, and improvisational mark-making, refusing to treat textiles as static. Instead, he creates cloth with motion, music, and selfhood.

Photography plays a strong role in his process. Jones merges photographic portraiture with textile construction to ask what it means to hold an image of oneself. A photograph documents; a textile protects. When these two mediums are combined, identity becomes layered, stitched, broken, repaired, and ultimately remade. His portraits do not simply represent subjects—they become part of the fabric itself, literally sewn into the story. Through this merging, Jones treats cloth as a container for lived truth, rather than as mere surface.

His artistic research reinforces this direction. Jones studies African American visual history, analyzing quilt archives, cultural textiles, and generational objects. His work acknowledges that quilts historically served as markers of love, survival, and communication within Black communities. Many quilts were created by women whose stories were not recorded elsewhere. Jones continues that story, not through imitation, but through expansion. By altering form, scale, and materials, he challenges what a quilt is expected to do.

This connection to storytelling becomes especially visible in Happy Tears (Lil Poppa), a quilt completed in 2025 and photographed by Anna Powell Denton. This artwork draws inspiration from a Lil Poppa song, responding to its emotional duality—grief held beside gratitude, mourning balanced with relief. Jones uses textile language to echo musical expression. The quilt becomes both a visual translation of the track and a personal reflection on survival.

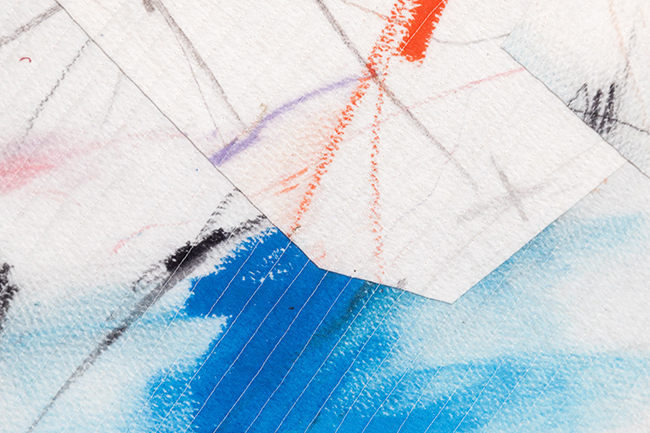

Seen from a distance, Happy Tears (Lil Poppa) appears as fragments of color arranged in rhythmic conversation. The palette is intentionally uneven: blocks of brightness meet darker tones, signaling the complexity of emotion within the song. Rather than symmetry, the work favors tension. Shapes press into each other; edges interrupt smooth continuity. This imbalance communicates a truth that music expresses well: emotional recovery is not clean. The body holds scars even as it celebrates.

Across the quilt surface, Jones’s stitches form repeated pathways that resemble musical beats. They pulse visually, moving the eye around the textile. These sewn lines echo breath, lyric, and rhythm. The viewer feels a sense of ongoing motion as if the quilt never fully rests. Jones treats stitching like handwriting—personal, imperfect, expressive. Every mark carries meaning.

Raw gesture appears throughout the work. Paint strokes, cut edges, and visible seams speak to honesty rather than polish. Nothing is hidden: the viewer sees labor, struggle, and release. The quilt resists silence and chooses vulnerability. Emotion becomes material.

The title, Happy Tears, guides interpretation. The tears described are not rooted in defeat; they form at the moment pain transforms. They represent a quiet victory—joy discovered after surviving fear, loss, or uncertainty. The quilt holds this feeling like an emotional shelter. It gives the viewer permission to celebrate survival without erasing hardship.

This artwork also reflects Jones’s connection to cultural inheritance. Quilts within African American history were often made without recognition or academic status; they served domestic and spiritual needs, not museum walls. By placing quiltmaking in direct conversation with music, portraiture, and contemporary art, Jones elevates the form without distancing it from its roots. His work preserves what quilting once meant while expanding what it can become.

Happy Tears (Lil Poppa) demonstrates Jones’s larger mission: to reinvent quilting through experimentation. His work pushes against traditional structure, creating textiles that look and behave differently from historical quilts. They operate like canvases, portraits, documents, and sonic fields all at once.

Within the broader art world, Jones stands as an artist who uses cloth to talk about identity rather than domestic function. His quilts remind viewers that history lives in fabric—that culture does not survive through words alone, but through touch, stitch, and memory.

Through storytelling, musical influence, stitched mark-making, and photographic integration, Julian Jamaal Jones continues shaping a new language for textile art. Happy Tears (Lil Poppa) is more than an artwork; it is evidence of an artist who understands how to hold memory and possibility in the same space.