Miguel Barros is an artist whose work challenges us to think deeply about our relationship with the environment. Born in Lisbon in 1962, Barros carries the cultural imprint of three countries—Portugal, Canada, and Angola. This wide lens of experience has shaped his art, giving him a sense of perspective that stretches beyond borders. In 2014, he left Angola for Calgary, Alberta, a move that opened new ground for creative exploration and growth. Trained in Architecture and Design at IADE Lisbon in 1984, Barros brings structure and imagination into balance. His paintings are not bound by rigid frameworks but infused with freedom, fluidity, and the imperfect textures of life. For him, painting is less about reproducing reality and more about opening a dialogue between memory and place. His art speaks of roots, longing, and belonging—always returning to Portugal, even as it moves restlessly through the present.

Colors of Lusitanian Lands

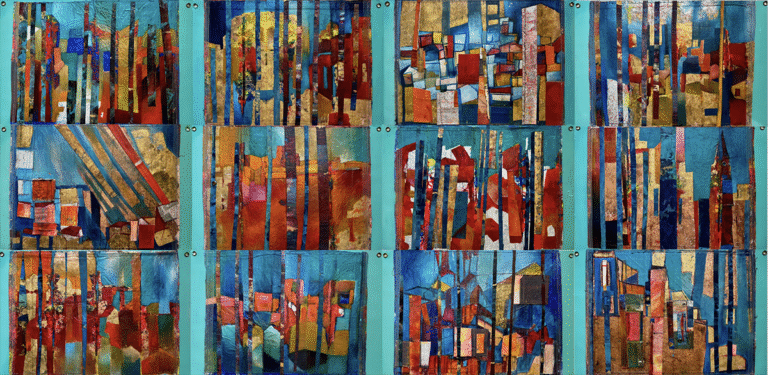

Miguel Barros’s upcoming collection, Colors of Lusitanian Lands (2026), is both a return and a departure. It gathers 30 oil paintings on silk and cotton canvas, all made with mixed media techniques. Each painting is part tapestry, part memory, part confession. Barros calls it an exploration of the intersection between dream and desire, where imagination brushes up against the material world.

What stands out immediately is his decision to leave the works unframed. They are not pinned down or confined. They hang loose, alive, swaying with air currents, never fully still. This refusal of the frame is not just aesthetic—it is a statement. He wants the paintings to breathe, to echo the rhythms of wind and ocean, to resist the museum hush of permanence. Like cloth that moves with the body, the works move with the air, hinting at impermanence, reminding us that all beauty is in motion.

Barros leans into imperfection, deliberately letting it guide the outcome. He breaks away from polished precision to embrace texture, fracture, and unevenness. This rawness is what he calls “perfect imperfection.” It is a paradox, but it makes sense in his practice. By refusing polish, he discovers honesty. The hand of the artist remains visible—brushstrokes, scratches, threads of fabric exposed. These flaws become part of the language, telling us that truth is found not in gloss but in what resists smoothness.

The collection is deeply personal. Barros describes it as painting his roots, as if each canvas were an excavation of memory. Portugal runs through it—the landscapes, the colors of sea and soil, the weight of history and the pull of longing. But these are not literal depictions. Instead, they are emotional cartographies. Red is not just red; it is the heat of Lisbon rooftops. Blue is not just blue; it is the Atlantic horizon stretching endlessly west. Gold whispers of ancient sun on stone. In these colors, Barros paints not the country itself but the sensation of belonging to it.

Distance, however, sharpens memory. Living far from Portugal, Barros has discovered that identity does not weaken with distance. Instead, it grows more insistent, more urgent. The collection emerges from that tension—being away yet being deeply tied. He shows that borders cannot contain the feeling of being Portuguese. The paintings speak to this paradox: you can be far, yet still entirely of a place.

The works also push toward universality. Though rooted in Lusitania, they carry meanings that cross cultures. Barros finds in his materials—silk, cotton, oil, pigment—a universal language that bypasses words. Viewers don’t need to share his memories to connect with the movement of color, the unframed dance of cloth. His art moves beyond geography into something more elemental.

What lingers is the sense of memory being kept alive through practice. Barros paints not just images, but acts of remembrance. Each painting is a ritual, a return, a re-living. He creates spaces where personal history meets collective feeling, where private longing becomes something that others can step into. His brush keeps alive what time and distance might otherwise erode.

In Colors of Lusitanian Lands, the past does not stay buried. It breathes. It flutters like cloth in wind, imperfect, moving, alive. For Barros, painting is not about fixing a memory in place but about allowing it to remain restless. His work insists that memory, like the sea, must move to stay alive.