Oronde Kairi works out of Germantown, Philadelphia, where the walls of his studio pulse with color, sound, and story. His art doesn’t sit quietly. It sings, moves, and remembers. Through bold lines and vibrant palettes, Kairi paints the texture of Black life in America—urban scenes, icons, music, everyday moments turned monumental.

What makes Kairi’s work feel alive is how deeply it’s rooted in rhythm. Not just visual rhythm, but cultural rhythm—the kind you hear in soul records, see on street corners, and feel in childhood memories. He leans into the beauty of daily life and gives it gravity. Whether it’s a nod to a legendary soul singer or a quiet street jazz scene, his work makes space for joy, pride, and reflection. And from his Philadelphia neighborhood, Oronde Kairi keeps doing what he does best—turning life into art that speaks.

The Work: “Marvin Gaye Studio Sessions 1”

Some paintings don’t just show a person; they let you hear them. That’s what happens in “Marvin Gaye Studio Sessions 1.” You can almost feel the hum of the microphone, the warmth of the recording booth, and the hush that falls right before a take. Oronde Kairi doesn’t just paint Marvin Gaye—he paints the sound of Marvin Gaye.

The work focuses on a specific moment in time—Marvin recording the Let’s Get It On album. Kairi sets the scene with care. Marvin is dressed in his now-iconic red skullcap and blue denim suit, headphones on, clasped hands, eyes closed, lost in the emotion of the music. Every detail feels intentional—the vintage reel-to-reel recorder, the wooden panels lining the walls, the slightly warm, golden tone that bathes the scene in nostalgia.

This piece isn’t a generic tribute. It’s precise, reverent, and anchored in history. Kairi clearly did his research, but what stands out most is the feeling. There’s a softness in Marvin’s pose, a kind of sacred energy. Kairi isn’t painting celebrity—he’s painting devotion. The studio becomes a sanctuary, and the viewer becomes a quiet witness to a man fully in his element.

Sweet Prince of the Ghetto

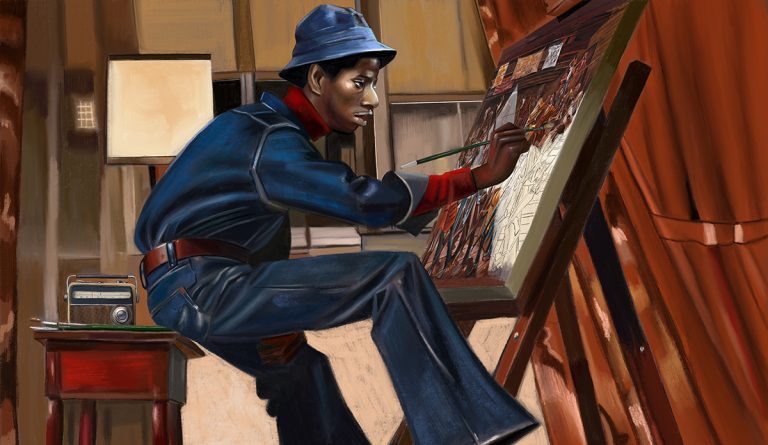

“Sweet Prince of the Ghetto” is another work that turns cultural memory into visual celebration. This time, the subject is Jimmy Walker’s character JJ from Good Times. Inspired by the stylized energy of Ernie Barnes, Kairi captures JJ mid-creation, deep in the process of painting The Sugar Shack, with music playing in the background.

The setting is familiar—the Evans family living room. But Kairi adds his own flair. JJ, dressed in his trademark denim, is painted with elongated limbs and rhythmic flow, echoing the Barnes aesthetic but with a modern edge. There’s movement in the scene, but also focus. JJ isn’t clowning. He’s working. Kairi uses this moment to reclaim and celebrate JJ as more than comic relief. He’s an artist, a cultural anchor, a reflection of Black creativity during the 1970s.

This painting honors not just one character, but an entire era. The textures, the furniture, the color palette—it all calls back to a time when Black families watched their lives unfold onscreen, often for the first time. Kairi’s brush carries that memory forward.

Midnight Melody

“Midnight Melody” strips away the noise. It’s a quieter piece, but it stays with you. A saxophonist stands alone beneath a streetlamp, his shadow cast down an empty alleyway. The music isn’t pictured, but you hear it—or at least, you feel its presence in the air.

There’s something ghostly about this scene. Kairi leans into atmosphere—the dim light, the texture of cobblestones, the solitary figure who seems halfway between this world and the next. The mood is jazz, but not performance jazz. This is back-alley jazz, late-night jazz, soul-heavy jazz. It’s music as memory, as escape, as prayer.

Unlike the brighter, more detailed works, this one breathes in the space it leaves open. It invites the viewer to imagine the sound, to fill in the silence. It’s about longing, and music’s uncanny ability to linger even after the last note fades.