Art

Maxwell Rabb

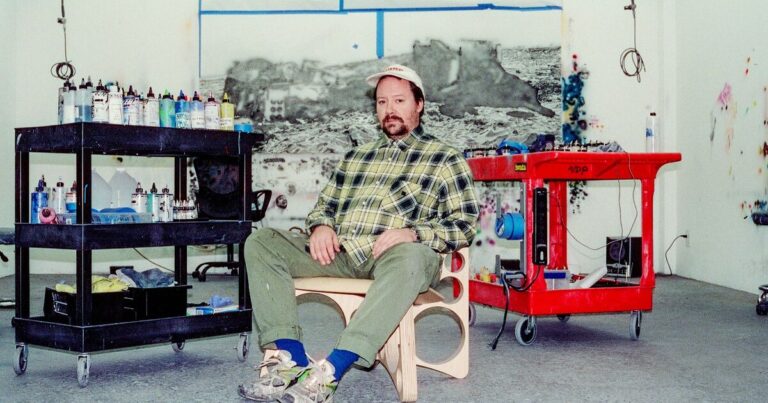

Portrait of Sayre Gomez. Photo by Sam Ramirez. Courtesy of Xavier Hufkens.

As a young man, Sayre Gomez worked in a photo lab. This work offered Gómez—who was studying at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago—a rare vantage point from which to observe the city. There, he witnessed city life through the eyes of strangers, and these unfiltered images stayed with Gómez, sparking his love for scenes of urban decay. Over the years, he began to collect photographs, found and taken by himself, to compile an archive that would later lay the foundations for his approach to painting, often of photo-realistic but semi-fictionalized urban landscapes.

Then, in 2006, Gomez moved to Los Angeles for her master’s degree at CalArts, and has called the city home ever since. “This place is wild,” Gomez said of the city. “I’ve been here almost 20 years and I’m still blown away quite regularly.” His paintings, quickly influenced by the urban sprawl of Southern California, synthesize images from his archive, his personal experiences, and more recently from the Adobe Stock catalog to portray the backdrop of contemporary life. Indeed, his canvases often evoke the ruinous byproducts of capitalism. Burnt cars, industrial machines, piles of garbage and burning shopping carts: these motifs feature prominently in Gómez’s work “Heaven ‘N’ Earth,” which can be seen at Xavier Hufkens in Brussels until March 2.

Sayre Gomez, view of the “Heaven ‘N’ Earth” installation at Xavier Hufkens, Brussels. Courtesy of Xavier Hufkens.

The title of the show reflects the viewer’s journey from “heaven” to “Earth” with works spread across the four floors of the gallery, as experienced when descending from the upper level. Under a skylight, the upper level features mixed media sculpture Scale replica of the past, present and future (Peabody Werden House) (2023), a diorama of a white boarded-up house, presented among several luminous sunset paintings, a juxtaposition of historical decay with idealized backdrops. The lower levels of the gallery feature Gomez’s photorealistic paintings, known as “X-Scapes,” paintings of material degradation in urban Los Angeles executed with trompe l’oeil, using airbrush, stencils, and other methods typical of Hollywood set painting.

Gómez often manipulates these urban scenes to emphasize their strange contradictions. His painting Creator of progress (2023) depicts a huge and ominous “cold mill” blocking a pristine landscape of Los Angeles and the light purple San Bernardino Mountains. Free of smog and pollution, the dreamlike, glittering cityscape appears out of reach, just beyond the industrial megalith. This stark contradiction is crucial to Gómez’s work, a commentary on the disparities between LA’s glamorous image and its stark reality. In turn, the artist hopes to instigate a truer understanding of the world.

Portrait of Sayre Gomez. Photo by Sam Ramirez. Courtesy of Xavier Hufkens.

Sayre Gomez, Family Room2023. Courtesy of Xavier Hufkens.

“We see the world through a fairly complex encryption system, and even in our daily experience, we see it through the photos we take, the maps we’re looking at, and the stream of images that are constantly flooding our experience,” Gomez said. “We all know it in some way, but I think you lose sight of it. . . . Somehow it’s more meaningful, more truthful. It’s like that Picasso quote, the lie that tells the truth. That way it becomes more revealing.”

His 2023 painting We pay in cash, which shows a charred car surrounded by trash against the Los Angeles skyline, symbolizes the chaotic remains of public life in late capitalism. But more notably, it features a stack of signs to the left of the painting, including ads for the stimulant Kratom or “Fast Divorce.” Here, Gómez shamelessly manipulates these photorealistic scenes, superimposing details and objects that prove the authenticity of the image. Playing with reality, it highlights the ease with which digital culture can distort information.

“Photography doesn’t have the same credibility as it used to,” Gomez said. “First, with Photoshop … a photo can be completely manipulated in seconds. That’s relatively new to the general public. Now with AI, people say, ‘It could be real, it couldn’t be, but I don’t know.’ People are just accepting that now.”

Sayre Gomez, creator of progress, 2023. Courtesy of Xavier Hufkens.

The 42-year-old painter is now a father of two, beginning this new chapter in 2020 as the pandemic unfolded. Today, Gomez thinks of her children as her biggest inspirations. Although the themes and subjects of his paintings have not changed dramatically over the past four years, his approach to these ideas and issues has evolved with his children in mind, taking a more practical perspective on the problems plaguing contemporary society.

“The things that I used to find fascinating and exciting have become much less sensational,” Gomez said. “Now, here’s another thing I have to learn to deal with more realistically: how am I going to talk to [my kids] about that? Or what will this look like in our lives? I mean, it’s crazy — being a parent right now or a parent right now is pretty crazy.”

Sayre Gomez, We pay in cash2023. Courtesy of Xavier Hufkens.

One of these paintings is Family Room (2023), which depicts two children digging in the dirt under a dilapidated restaurant sign that read “The Family Room”. Gomez noted that this artwork is tinged with melancholy, paralleling a personal memory of him watching his children play in the mulch while two children across the street from his studio played near a makeshift RV park. Throughout, Gómez is aware of the class divisions that rub across Los Angeles, a problem that points to a broader trend. “You can look at New York in the ’90s as the rubric or the model for capital coming in and taking over, taking over a city and turning it into something much more class-oriented, especially upper-class,” he added.

In works like daily mail e Page 6 (both 2023), each depicting a burning shopping cart, on the lower floor of the gallery, Gómez directly addresses themes of abandonment by focusing on objects that symbolize the transitory nature of consumer culture. These paintings, like much of his work, serve as metaphors for the use of everyday objects, making us responsible as consumers of the world around us.

Gómez casts urban decay in a clear light, where the fringes of capitalism and development are brought to the light of the sun for all to see. Here, he hopes to find some truth in the juxtapositions of beauty and blight.

Maxwell Rabb

Maxwell Rabb is the staff writer for Artsy.