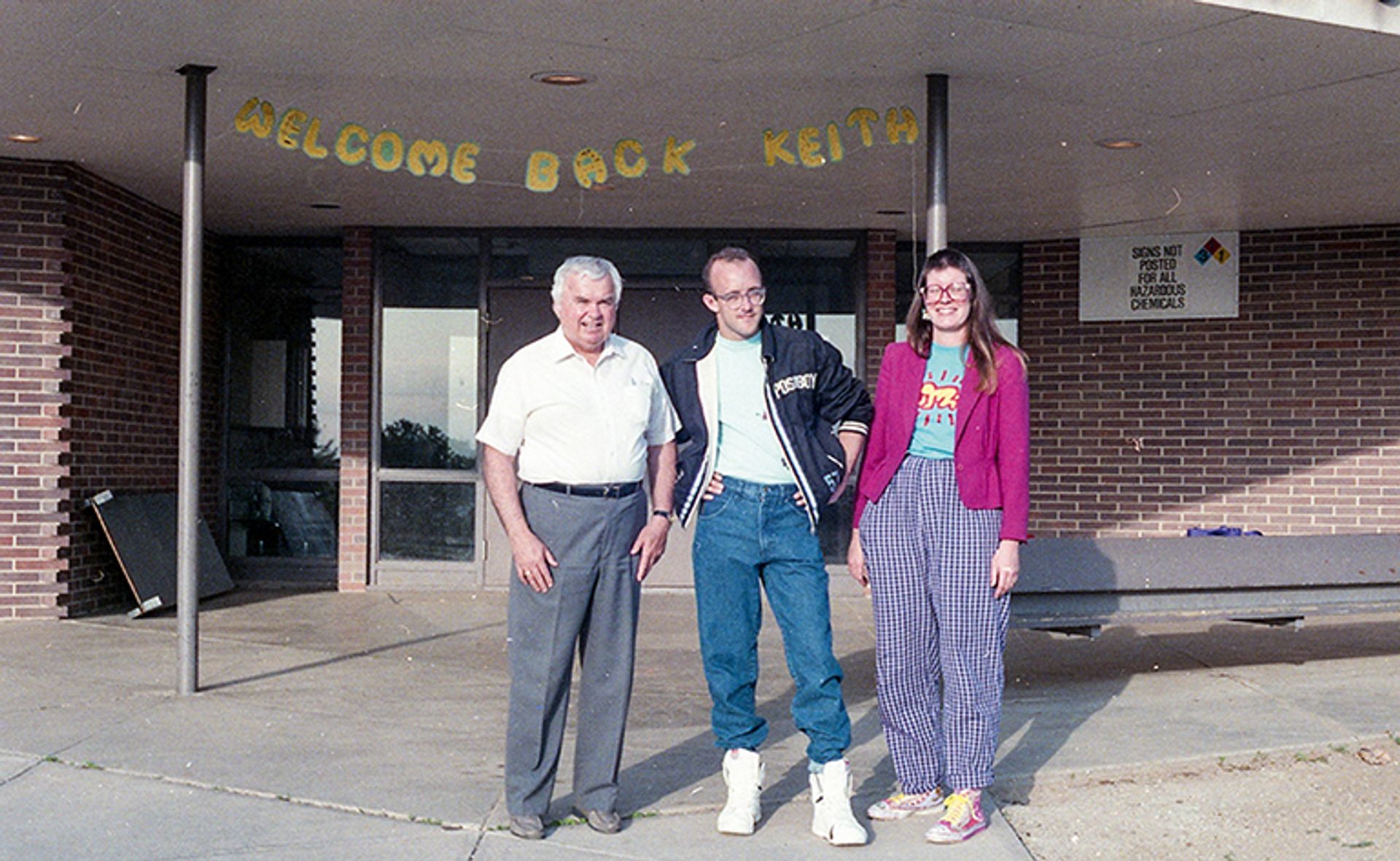

Keith Haring was able to paint the brightly colored mural in the library of an Iowa City elementary school in a single day, but it was the culmination of years of correspondence with his students. He first visited Ernest Horn Elementary School in 1984, during a residency arranged with the University of Iowa after an art teacher at Horn, Colleen Ernst, initiated a pen-pal exchange. His letter writing continued in the following years, although Haring’s fame grew; students sent him a VHS of themselves singing Happy Birthday, which Haring said was a favorite gift.

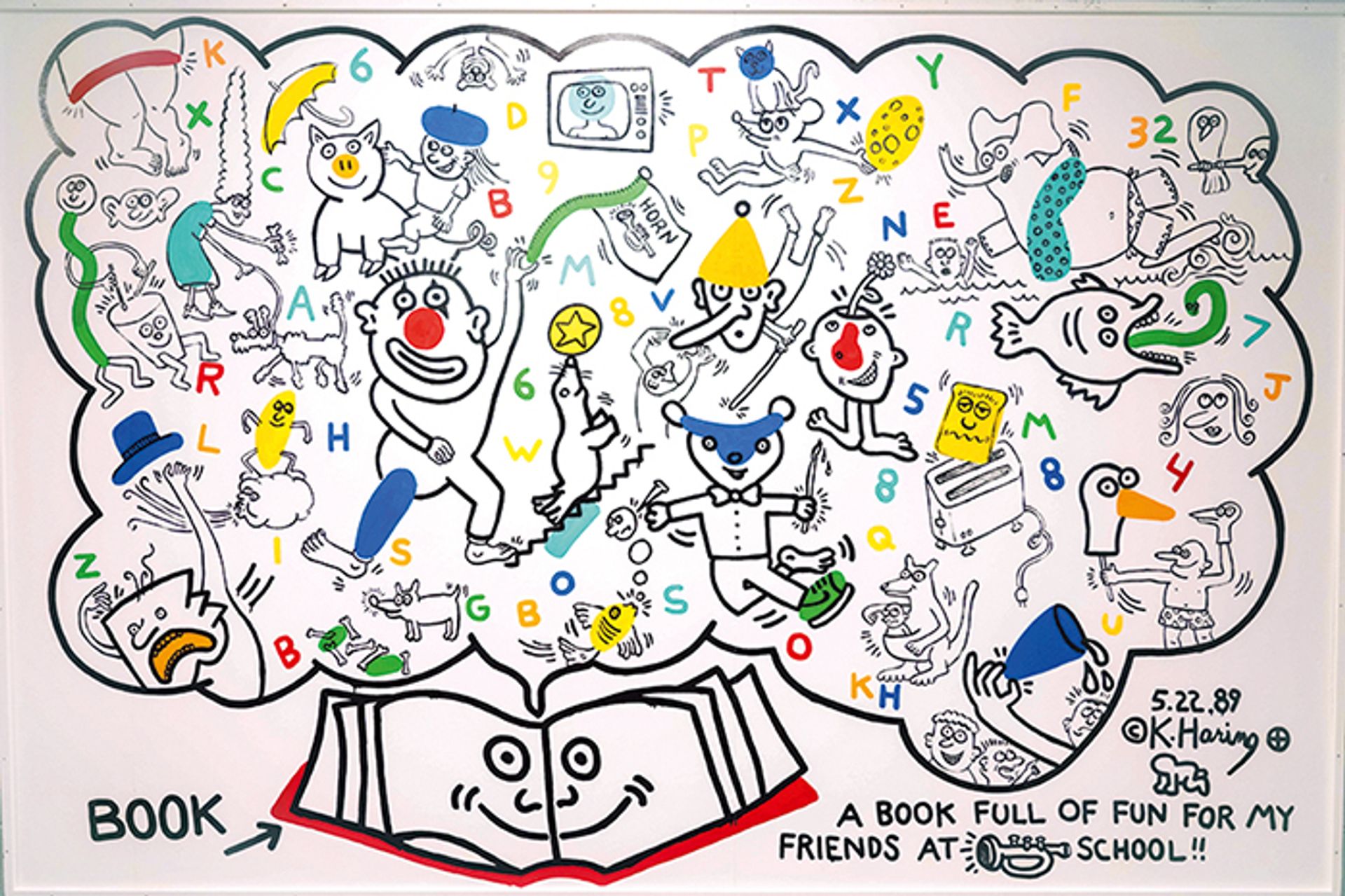

When he returned on May 22, 1989, Haring created the mural as a gift for the school, improvising – with input from the students – an illustrated bubble emerging from a book. He started with a variety of shapes, lines and letters that he then transformed, such as a folded patch of turquoise that became the rubber ring around an elephant falling from a surfboard between the letters “E” and “F.” An orange triangle became the beak of a duck, and a red circle served as the nose of a clown waving a flag with the image of a horn. This pictogram for “horn” is used again in Haring’s inscription at the bottom: “A book full of fun for my horn school friends!!”

A few months later, Haring would share publicly that he had been diagnosed with AIDS, dying at age 31 less than a year later on February 16, 1990. He had not shared his diagnosis before his visit to the school in 1989, but confided in Ernst after a hematoma is noted which was actually Kaposi’s sarcoma. Horn later organized an AIDS education event, and Haring wrote to the school: “It’s amazing to me that the school took the initiative to institute a discussion about AIDS, mainly because of the students’ contact with me (and taking care of me). It makes me proud that I had the courage to talk about it in the first place. Education is the key to stopping this!”

On public view for the first time

Set as it is in a small-town Midwestern school, A book full of fun is one of Haring’s lesser-known murals. It is being exhibited to the public for the first time at the University of Iowa’s Stanley Museum of Art in an exhibition that will run from May 4th—coinciding with what would have been the artist’s 66th birthday—until January 7th, 2025. To my Horn friends: Keith Haring and Iowa City it contextualizes the mural with works lent by the Keith Haring Foundation, archival ephemera and photographs related to his visits to Iowa City and the history of the mural’s recent conservation, which entailed its removal and the entire wall on which it was painted in the school.

In 2022, the Stanley was contacted by Horn about the mural ahead of a renovation project. However, at the time the museum was about to reopen after 14 years of closure following the loss of its building to a flood. “I didn’t have a lot of bandwidth, but I went out to look at the mural and realized it was wonderful,” says Lauren Lessing, Stanley’s principal. The Journal of Art. “They were about to undertake a renovation project at the school, and the mural itself was on a wall that was scheduled to be demolished in the summer of 2023.”

The finished mural

© 2023 University of Iowa

Recognizing how special the mural was, the museum partnered with the school in its conservation, with the Keith Haring Foundation and the Henry Luce Foundation also joining the project. Initially, it looked like it would be relatively easy to remove the plywood panels on which the mural was painted from the wall, but it soon became much more complicated. The panels were glued and screwed to the wall, and what Haring had painted was a layer of plaster placed over it. Because these panels were so tight to the wall, cutting behind them proved impossible, and drilling from the other side of the wall revealed that there was asbestos inside that required safe removal. Finally, both the mural and the wall were cut as a 1,800 kg object, with the mural supported by an acrylic support and a rigid frame. The structure was carefully moved to the museum at night, with a police escort to avoid stops and traffic. Although consideration was given to removing the cinder blocks from the panels, they ultimately stayed together.

“From a historical and curatorial point of view, we believe that the mural and the wall tell a more complete story and honor the material creation of the mural as part of the Ernest Horn Elementary School library,” explains curator Nina Roth-Wells.

Even after years of student enjoyment, the mural was in good condition and did not require extensive treatment. “Since the mural was installed in a windowless room, there was no color fading due to exposure to natural light,” says Roth-Wells. “The mural was glazed with plexiglass that had quite a few scratches and adhesive residue, but the mural itself was pristine.”

“An important story to tell right now”

Alongside this conservation process, Stanley’s exhibition will highlight how Haring used art for community engagement and activism. “It’s a very important story to tell right now, about the way this small town in Iowa opened its arms to an avant-garde graffiti artist whose work was somewhat controversial and who might not have been welcome elsewhere,” says Lessing. . One of the works that can be seen will be Haring’s print Ignorance = Fear, Silence = Deathmade in 1989 to draw attention to the AIDS crisis.

In the midst of addressing health issues in her life and art, Haring continued to make time to visit schools and collaborate with children; in early May 1989, he had painted a 488-foot mural in Chicago’s Grant Park with about 500 local students. No Iowa City Press-Citizen article about Horn’s mural published on May 23, 1989, Haring said of working with young people: “For me, it’s the most difficult audience. They are the most honest… They have fresh ideas and good imagination.”

While at the school, Haring drew portraits of the children, took photographs and talked with them. Some of the drawings, as well as oral histories collected from the community, will be part of Stanley’s exhibit.

Students recall that he took his artistic voices seriously

“Many of the people we interviewed are former students of Ernest Horn Elementary School, and they fondly remember the warmth, generosity and respect that Haring showed them,” says Diana Tuite, curator of the exhibition. “They remember that he took his artistic voices seriously.”

Paul E. Davis, the school principal, with Keith Haring and art teacher Colleen Ernst

Courtesy of Colleen Ernst

The mural will be reinstalled at the school in 2025, its scratched Plexiglas replaced with anti-reflective glass, while new environmental controls and lighting will ensure its interconnected characters can delight students for years to come, now sharing a lesson in not only embracing creativity . but to take care of art and people.

“I think it’s important to think of the artwork as a legacy that we’re responsible for,” says Lessing. “We are responsible for this mural that was left in our care by an artist whose career was too short. So we are its administrators. I think it’s a good thing to teach.”