Artist Doug Argue calls the Weisman Museum of Art’s (WAM) refusal to sell a monograph on his art in its bookstore during his recent survey exhibition there a form of “book banning.”

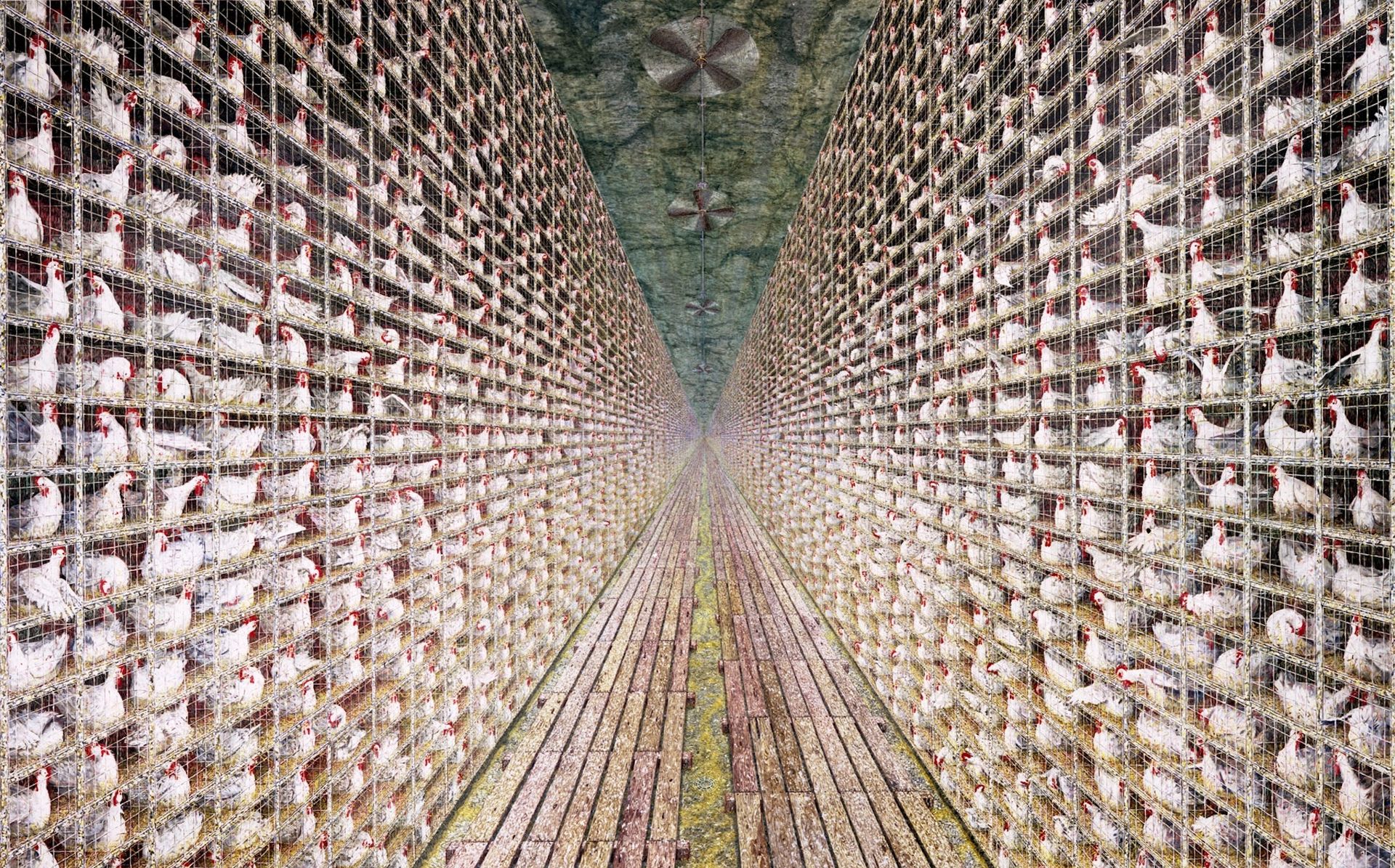

The exhibit, held last summer at the University of Minnesota museum, featured Argue’s work from the early 1980s. Argue’s work has been shown at One World Trade Center and the Venice Biennale. He is best known in Minnesota for his giant painting of a chicken coop in a factory, which can be seen for many years at WAM.

A work originally selected by guest curator Elizabeth Armstrong for the show, Doug Argue: Letters to the Future (June 17-September 10, 2023), which depicts a boy with an electrical cord around his neck, was “censored,” according to Argue. “They said if anyone saw it, they might kill themselves,” he said at a lecture at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. in January Argue was inspired by Rembrandt Lucretia (1666) and the death of his brother in a traffic accident due to the work.

Doug Argue, No title1983 Courtesy of the artist

“Every day we make decisions about how an exhibition is mounted,” WAM director Alejandra Peña-Gutiérrez wrote in response to questions about Argue’s show. “Those choices are driven by practical concerns: financial constraints, shipping logistics, gallery space considerations, as well as curatorial choices.”

Although it has the same title as the show…Doug Argue: Letters to the Future (2020): The catalog was independently produced by Skira. Argue says he learned it wouldn’t sell at the bookstore the day after the book’s publisher, Claude Peck, opened the exhibit. Then he called it Peña-Gutiérrez. “It was a very brief conversation,” says Argue. “All he said was: ‘the conqueror’.”

Several works reproduced in the catalog, all made in 1990, present Europeans mutilating, caged and decapitated indigenous figures. Another painting in the catalog, hung up (1989), depicts hooded figures hanging from a gallows.

“My piece was about the education I received and how it whitewashed,” says Argue. “It’s not like I’m taking someone else’s story. I’m taking my own story, and I’m protesting the fact that we didn’t learn any of that when I was in school.”

Doug Argue, chickens1994 Armenian Museum of Contemporary Art, courtesy of the artist

According to Peck, the idea came while working on the book to have a complementary sample of Argue’s work at WAM. At the end of the process, former WAM director Lyndel King wrote a foreword for the book. In 2020, King retired, then the show was postponed due to Covid-19. Peña-Gutiérrez became director in 2021. After the opening, Argue says copies of the catalog he had signed at WAM were sent to the Cafesjian Art Trust in Shoreview, Minnesota.

“We had no problem with the original title of the exhibit, and I saw no problem with keeping it when it was finally presented last summer,” Peña-Gutiérrez wrote.

The content of the book was another matter. “Arts organizations like ours must be accountable to their communities for the decisions they make,” Peña-Gutiérrez wrote. “There are several images of artwork in the artist’s book that are culturally insensitive and presented without context. While the artist is responsible for their creative choices, I have a responsibility to ensure that what Weisman supports aligns with our values.”

Doug Argue, Untitled (bar scene)1987 Collection of the Weisman Museum of Art. Image courtesy of Weisman Art Museum

The conflict over Argue’s work illuminates the challenges museums face as they try to be more inclusive while navigating an increasingly politicized climate around free speech on campus and the ways American history is told. That process is not linear, according to Kelli Morgan, director of curatorial studies at Tufts University, who works with museums on anti-racism initiatives.

The moment of change brought about by the Covid-19 pandemic and the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor in 2020 “really showed that the systems themselves have to change, and for that to happen, white people, especially white Americans, are go. have to sacrifice,” says Morgan.

Even before 2020, controversies arose around white artists creating work about historical atrocities against black and indigenous communities. “There’s a white privilege that assumes knowledge, and not just assumes knowledge in terms of knowing, but actually knowing better,” Morgan says. “I have access to this that I can talk about, even though I have no literal, even figurative, relationship or knowledge about it.”

Doug Argue, School of fish 22021. Courtesy of the artist.

Museums have been at the center of these debates in recent years, including the Walker Art Center’s decision in 2017 to remove Sam Durant. Scaffolding (2012) from the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden and calls for the Whitney Museum of American Art to withdraw Dana Schultz’s painting of Emmett Till’s Mutilated Body from the 2017 Whitney Biennial. More recently, Philip Guston’s just-ended retrospective at the Tate Modern has been postponed due to concerns over its paintings depicting members of the Ku Klux Klan.

Aaron Terr, director of public advocacy for the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, says Argue’s case may not necessarily be a violation of the First Amendment. “But the motivating factor behind the removal you can certainly say is at odds with the basic mission and purpose of a public museum,” says Terr. “A museum should oppose the idea that some art should be shielded from public view because it is inappropriate.”

“Was it censorship? I don’t know,” says Peck. “I don’t want to argue the semantics. For me, the book was effectively banned.”

Curator Elizabeth Armstrong wrote in a statement that she was not consulted about the removal of the bookstore’s catalog and that the action prevented visitors from experiencing the broader range of Argue’s work. “A reflexive fear of people’s reactions, and an increase in censorship and the cancellation of culture in these bastions of learning, is a disturbing trend,” he wrote. “It undermines the opportunity and the obligation that museums have to educate and challenge their public.”