Vicky Tsalamata is based in Athens, Greece, and her print practice moves with a double vision: it looks backward into literature and moral allegory while staying locked onto the pressure points of the present. Her work circles around a familiar question—how people live together, and what they become inside systems that reward the wrong things. She borrows the wide-angle framing of Honoré de Balzac’s La Comédie Humaine, but she isn’t illustrating the book or dressing up in tribute. She’s using it as a lens: a way to scan society’s patterns, its performances, its quiet cruelties, and its daily bargains.

What makes her approach hit is tone. There’s wit, but it’s not playful. It has bite. Tsalamata’s sarcasm doesn’t sit on top of the image like commentary; it’s built into the structure of the work. Her prints make space for contradiction—how a world can be hyper-connected and still feel isolating, how progress can coexist with moral collapse, how speed can pass for meaning. She asks the viewer to stop, not for sentiment, but for recognition: in a culture that measures worth with numbers and status, what happens to the rest of us?

That tension—between what’s promised and what’s real—runs through her major projects. Whether she’s charting the social terrain through La Comédie Humaine or tracking time’s relentless push in Impulse, Tsalamata keeps returning to the same core material: human behavior under pressure. The work is direct, sometimes unsparing, but it’s not hopeless. Under the critique is a plain insistence that communication still matters, that love and friendship aren’t optional decorations, and that the human scale of life can still be defended—if we choose it.

“La Comédie Humaine”

Tsalamata’s graphic work La Comédie Humaine starts with a title that carries a whole worldview. Balzac wrote a vast social panorama, one that treats society as an interlocking cast of ambitions, compromises, deceptions, and desires. Tsalamata takes that panoramic idea and folds in another reference—Dante’s Divine Comedy, where the poet imagines a moral architecture of consequence. Together, those two sources create a charged backdrop: the crowd of society on one side, the question of judgment on the other.

But Tsalamata’s position is contemporary, and her faith in neat moral outcomes is limited. Her work reads like a report from inside the machine, not a sermon from above it. The sarcasm is aimed at the modern condition: a world that keeps evolving socially and economically while somehow staying stuck in the same power habits. In her framing, the “grand scheme of things” doesn’t arrive as a comforting cosmic perspective. It arrives as a kind of pressure—an awareness that individuals can feel reduced, moved around, dismissed, treated as small units rather than lives.

The piece functions like a universal map, but not the kind you use to find a destination. It’s a map of forces: moral shifts, economic churn, social posturing, and the deep rot inside political and social systems. Tsalamata describes a reality where the weak are crushed while the corrupt grow stronger, more protected, and more shameless. What’s sharp about her statement is that it doesn’t pretend this is new. She points to past and present, implying a repeating cycle—different eras, similar outcomes. Technology changes. Language changes. The pace changes. The pattern keeps resurfacing.

And then she pivots toward what’s missing. In the middle of critique, she calls out the need for communication between people—especially “now days,” in a time when connection is constant but contact can be thin. She names love and friendship as central, not sentimental. That matters because it gives the work an ethical anchor. Tsalamata isn’t only describing a broken system. She’s also reminding us what the system tries to replace: care, attention, loyalty, mutual recognition. The work becomes a demand for human presence, not just a depiction of its absence.

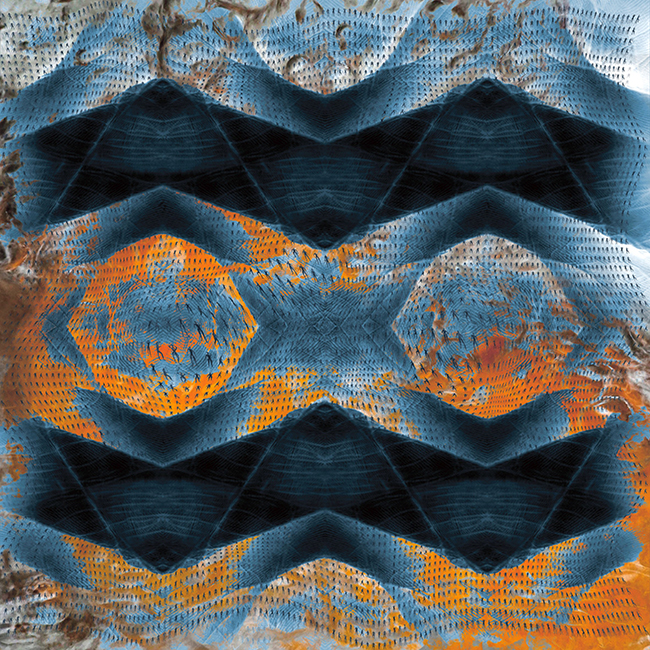

Her technique reinforces this sense of structure and accumulation. La Comédie Humaine is made through intaglio and mixed media combined techniques using seventeen iron matrices worked with intaglio processes. Seventeen matrices suggests a build-up of parts, an engineered complexity—like constructing a social diagram layer by layer. Iron brings an industrial severity, a hard material that suits a hard subject. It implies durability, resistance, and pressure: the physical reality of force, transferred through the press.

A related work, La Comédie Humaine B’, was selected and is displayed in the Main Exhibition of the Guanlan International Print Biennial Nomination Exhibition 2025 at the Guanlan Printmaking Museum, with dates running from December 20, 2025 through April 2026. That context places Tsalamata’s project inside a wider field of contemporary printmaking—where process, material choices, and the ethics of image-making sit in the same conversation.

“Impulse”

If La Comédie Humaine reads like a social atlas, Impulse behaves like motion. Created in 2025 as an edition of 45 for Patanegra Editions in Spain (52 x 38 cm), the work focuses on time—not as an abstract meditation, but as lived velocity. Tsalamata frames it through “kinetic momentum”: the force that keeps modern life moving, often faster than reflection can keep up.

Her subject here is familiar and still strange: how modern societies normalize speed, then act surprised when people feel detached from their own lives. She points to the way we ignore the rhythm of time, even while it governs everything—deadlines, routines, notifications, pressure. In her statement, people become passive spectators, watching real life run alongside them. It’s a haunting image because it’s quiet. No catastrophe is required. Just drift, repetition, and distraction.

The work links to Heraclitus—“Everything flows”—not as a decorative quote, but as a reminder that time doesn’t negotiate. You can’t pause the river. You can only decide whether you notice it. Impulse sits within Tsalamata’s larger project Awareness, an installation she presented at the Krakow International Triennial in 2024, and it extends into an international collaboration for 2026: the XII Graphic Arts Folder project, “XII Contemporary International Graphic Amalgam, 20 American Graphic and 20 European Graphic,” bringing together invited printmakers across regions.

In that setting, Impulse becomes both personal and collective—an individual statement that also fits a shared format: the edition, the folder, the transfer of pressure into image. That connection is fitting. Printmaking is time-based in its own way: it asks for sequences, stages, returns, patience. Tsalamata uses that discipline to speak about the opposite—our era’s impatience—and to ask what it would mean to reclaim attention before time runs off with the day.

Conclusion

Tsalamata’s prints don’t soften the truth to make it easier to digest. They stay crisp, ironic, and precise—showing how power behaves, how speed reshapes living, and how isolation can hide inside constant connectivity. Yet beneath the critique is a steady, human ask: slow down enough to see each other, to speak honestly, to choose love and friendship as real forces. In her hands, printmaking becomes a record of pressure—and a reminder that attention is still a form of resistance.