Established Los Angeles artist Henry Taylor is having something of a renaissance. Taylor was thrust into the spotlight in 2017 when her painting of Jay-Z appeared on the cover of the New York Times style magazine. T. A major exhibition of his works is currently on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York (until January 28, 2024). It was primarily in the spotlight in Paris earlier this year when a show of 30 new paintings, sculptures and works on paper opened at Hauser & Wirth (From sugar to shituntil January 7, 2024), inaugurating the new gallery space in the French capital. “Combining figurative, landscape and history painting, along with drawing, installation and sculpture, Taylor’s broad body of work is rooted in the people and communities closest to him,” the gallery said in a statement. This interview was originally published by our brother newspaper, The newspaper Art France.

The Art Newspaper: In June and July you moved into a studio in the Bastille district of Paris. Where did you visit and what did you see?

Henry Taylor: Bastille was nice, you know? The location of the apartment and studio was great. Downstairs were restaurants…a nice little patio. Friendly cats. Pigeons on my windowsill. It was great. I was taking French [lessons] Twice a week. I already had friends and knew people there.

I went to [see] The Who and the Kendrick Lamar concert. Kendrick came to my studio several months ago, that was the first time I met him. I worked hard, I felt obliged. There were so many blank canvases in the studio. I always make works when I travel, not necessarily for an exhibition but because I want to. This time I concentrated a lot.

Among the museums you visited in Paris, which ones had the biggest impact on you?

I went to the Picasso Museum. I went to see the Basquiat-Warhol show at the Louis Vuitton Foundation. I saw the Manet-Degas exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay. And I always want to go back and look at Bonnard and Vuillard, going straight to those guys.

I like going back to the d’Orsay. One thing is that museums don’t change. It’s like going back to your grandma’s house. In seventh grade, I had an English teacher, Teresa Escareno, who was very important to me. I also have a self-portrait of her, which was given to me by her daughter. So, at the d’Orsay, I think of her. I met her when I was in sixth grade because her husband was a physical education major [sports] trainer It was my first introduction to painting: to Cézanne and Vuillard, to Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. When I first started going to his house he went with the basketball team and we were next door talking about painting. She was my first introduction to Bonnard.

What do you mean by the title of the exhibition? From sugar to shit?

I was trying to invoke my mother in the show, maybe not just in the form of painting but in the form of words. That’s something she would say. So I thought of another title. And I came back From sugar to shit. It’s the idea that situations change and get worse. Some things are just sweet and then sour. That’s not being optimistic, I try to be a hopeful person but this is what I’m going through.

What did you paint in Paris?

There were so many blank canvases there, I had to assess the situation. If there were golf clubs there, I might have gone golfing. The canvas was there, and I think just because the materials were there, I felt compelled. I always work when I travel, but not for a show. I could have done six or seven large paintings and a few smaller ones. Some were from people I met in Paris. This girl from Gabon [or[ my friend Harif invited some people over one night and I painted them.

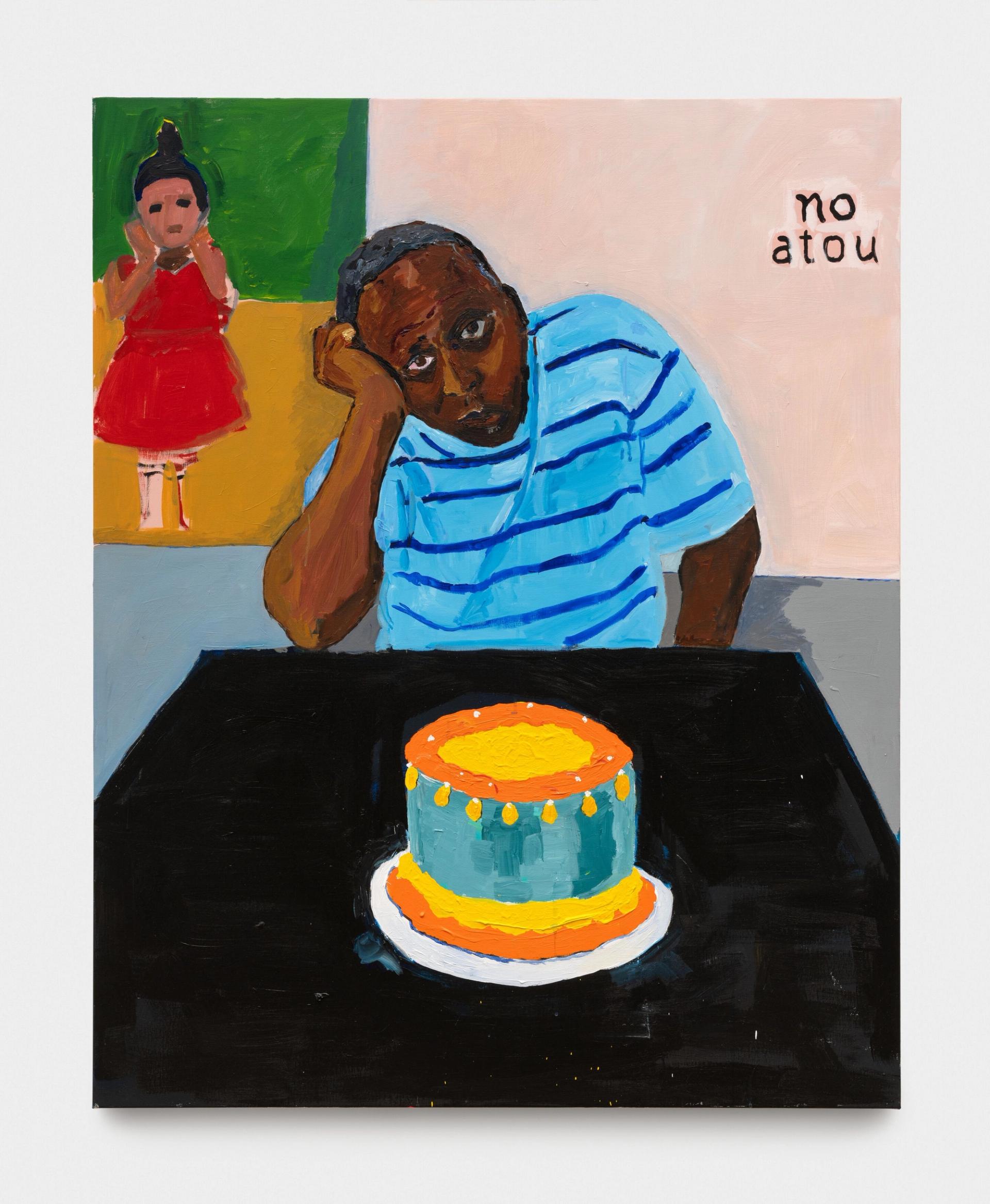

Henry Taylor, no atou (2023)

courtesy Hauser & Wirth

In the exhibition, there is also a self-portrait in which you wear a striped t-shirt reminiscent of Picasso.

My birthday was here in Paris. And my daughter sent me a cake, the most beautiful one I have ever received. So I thought of the painter Wayne Thiebaud and all the cakes he painted. And I said to myself that I couldn’t cut it, that I was going to look at it. And then there is the painting of my daughter that I painted here in the background. So that is me on my birthday. Perhaps this pose also comes from paintings that I looked at in history but it is mostly an image of being alone. And these words behind on the wall are from [Paul] Gauguin, I think it’s Tahitian slang, which means, “I don’t care.”

After ten years working as a psychiatric technician at the Camarillo State Mental Hospital, what led you to change direction and enroll at Cal Arts (California Institute of the Arts) where you received your degree in 1995?

My mom always said, “Put your best foot forward.” My brothers were athletes. I never thought of art as a career. They told me I would never make any money. I was a nurse for ten years. The paint was something I had put in a burn. I had a teacher, James Jarvaise [at Oxnard Community College], who was actually French and told me to apply to CalArts. And that’s what I did.

You often paint people who are close to you but also people you don’t know. Does knowing your model make a big difference?

One of my brothers was a barber, so I think of the heads of a barber shop and you want to get a nice cut! You can think of a different technique, but sometimes you just get lost. You only paint the body. It’s probably like the surgeon. It can be different with the traits or the girl: you want to appease; you don’t want to scare them.

Do you create your sculptures like you paint, gathering people around you or assembling objects you come across?

Sometimes it’s random, even in paintings. There is a form of spontaneity; I don’t really plan everything. I see someone, I ask them to feel for me and I grab the brushes. Likewise, I grab materials that resonate with me and then put them together. It takes time. Sometimes I need a hand. Sculpture is, to me, so new and fresh.

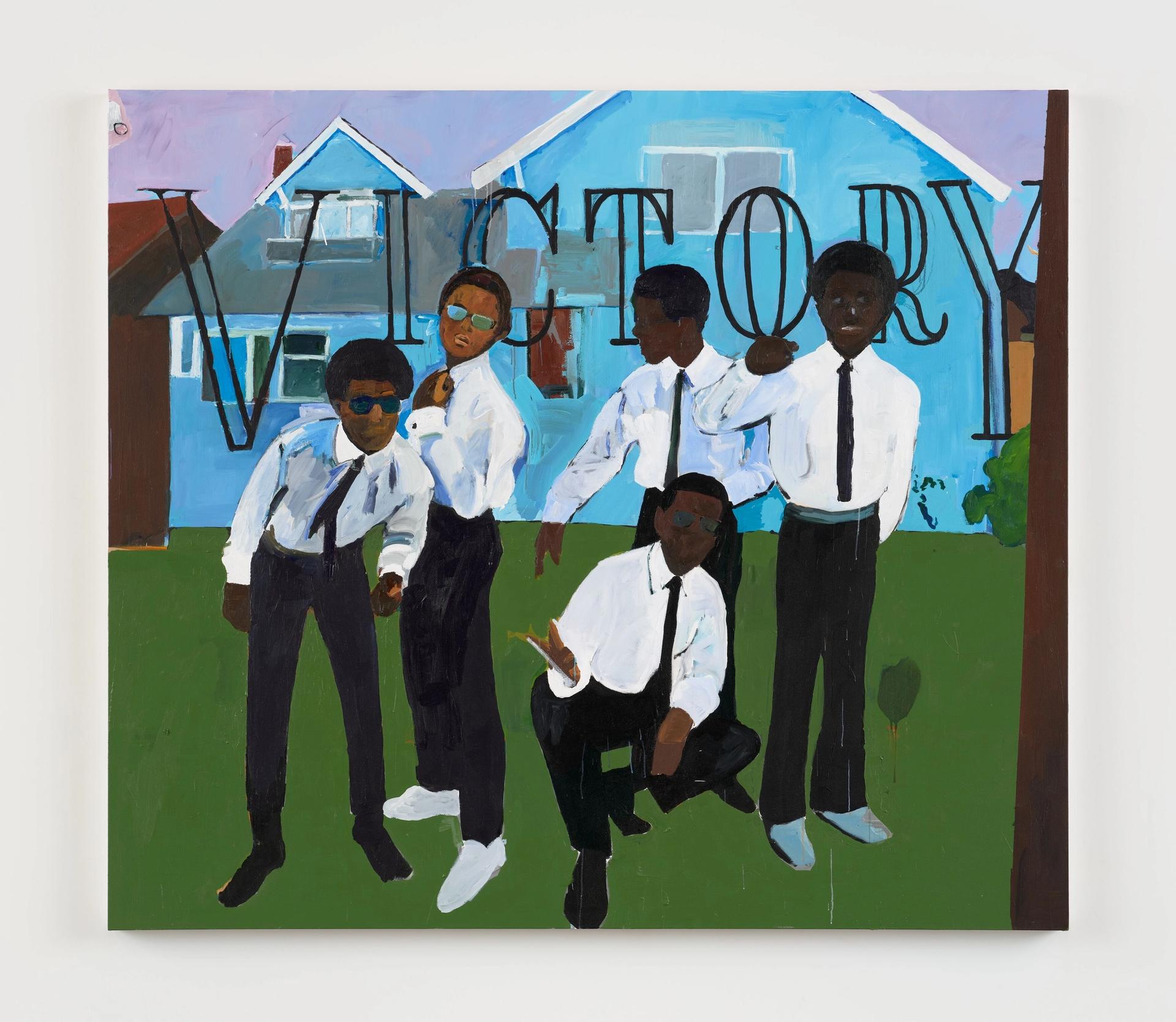

Henry Taylor, One tree per family (2023)

courtesy of Hauser & Wirth

How do you come up with the idea of a sculpture like One tree per family (2023), for example?

I was in my studio, thinking about my brother Randy, who was part of a movement that he introduced to me. I think about him and the things I learned from him. My brother went to Black Panther meetings [he was associated with the Ventura County chapter of the Black Panthers]. When we think of this movement, we think of iconic items like the leather jacket worn by the members. Hair is a connection to the 60s movement.

It’s my way of honoring my brother and all the people. It’s me reacting and being kind of nostalgic at the same time but also looking at what happened recently. Because then there’s also the Black Lives Matter movement. We are not being aggressive; we are playing defense here. It doesn’t have to be literal, you know? There is also a sense of pride. My brother is someone I look up to, to this day. He is always passionate and sincere.

Do you always paint in your studio?

no I went to Gorée [off the coast of Senegal], to Kehinde Wiley’s artist residency, Black Rock. I asked if I could stay an extra week and painted up to 20 minutes before my ride arrived. I tried to paint everyone who worked there. For my exhibition in New York in 2019 [at Blum & Poe gallery], I must have done a dozen paintings: Zadie Smith, Rashid Johnson, Derrick Adams, my daughter… I was going to my holes with my paint on an egg carton. I was in Colombia and I painted someone on the street. I would like to draw in museums but I’m a little shy. I paint everywhere.

Is travel important to you?

Yes, it is important. I am currently trying to arrange a trip to Burkina Faso, but they say they are having some problems at the moment, so I can go to Egypt, where I have never been. I think it’s time to go there. In my studio in Paris, I left two paintings [showing] pyramids I was thinking [Philip] a taste

How do you know when to stop?

You just have to find some time. Sometimes we don’t even know how beautiful things are. It’s like a Rothko and it’s really just a sunset over water: just two things, the horizon and the ocean. Why is it so beautiful and so minimal? Sometimes you see it every day, but you don’t really look at it.

If I look at an early Guston or [Willem] de Kooning and it’s already everywhere, you see people start taking less. sometimes [it’s] just the essentials: less is sometimes more.

Henry Taylor, I have brothers EVERY OVA in the world, but they forget we are related (2023)

courtesy of Hauser & Wirth