Archaeologists from the Jagiellonian University (JU) in Poland discovered an ancient Native American calendar at the Castle Rock Pueblo archaeological site in western Colorado, which contains the remains of an ancient settlement. Although the oldest petroglyphs found date back to the third century AD. C., JU researchers found previously unstudied rock panel work created in the 13th century, when the site was at its peak. Polish research team leader Radosław Palonka sees these findings as the start of a new discovery process, combining cutting-edge mapping technology and collaboration with local indigenous communities to better understand the area.

Castle Rock is the largest village in a sprawling complex of ancient settlements in Colorado’s Mesa Verde National Park. The villages, carved into rocks in the numerous canyons of the area, are characteristic of the Pueblo culture that flourished in the 12th and 13th centuries. After more than a thousand years of inhabiting the region, the Pueblo peoples developed advanced techniques for architecture, combining intricate rectangular rooms made of adobe into fortified terraced structures.. Favorite locations for construction were defensive positions, including the hilltops, mesas, and steep rock ledges present in the Castle Rock complex.

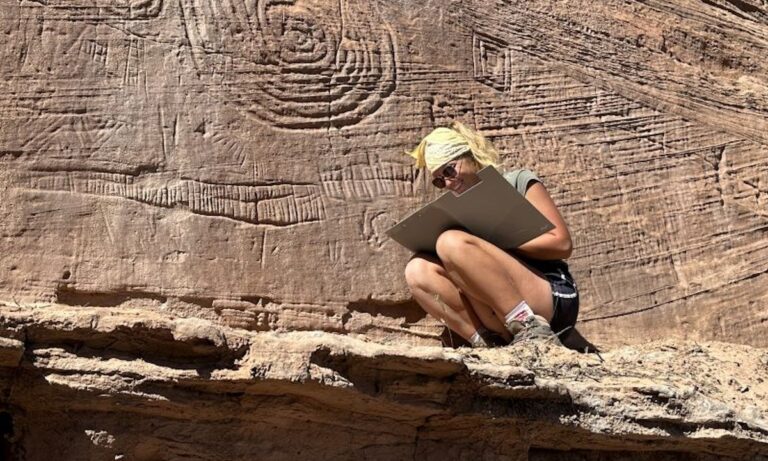

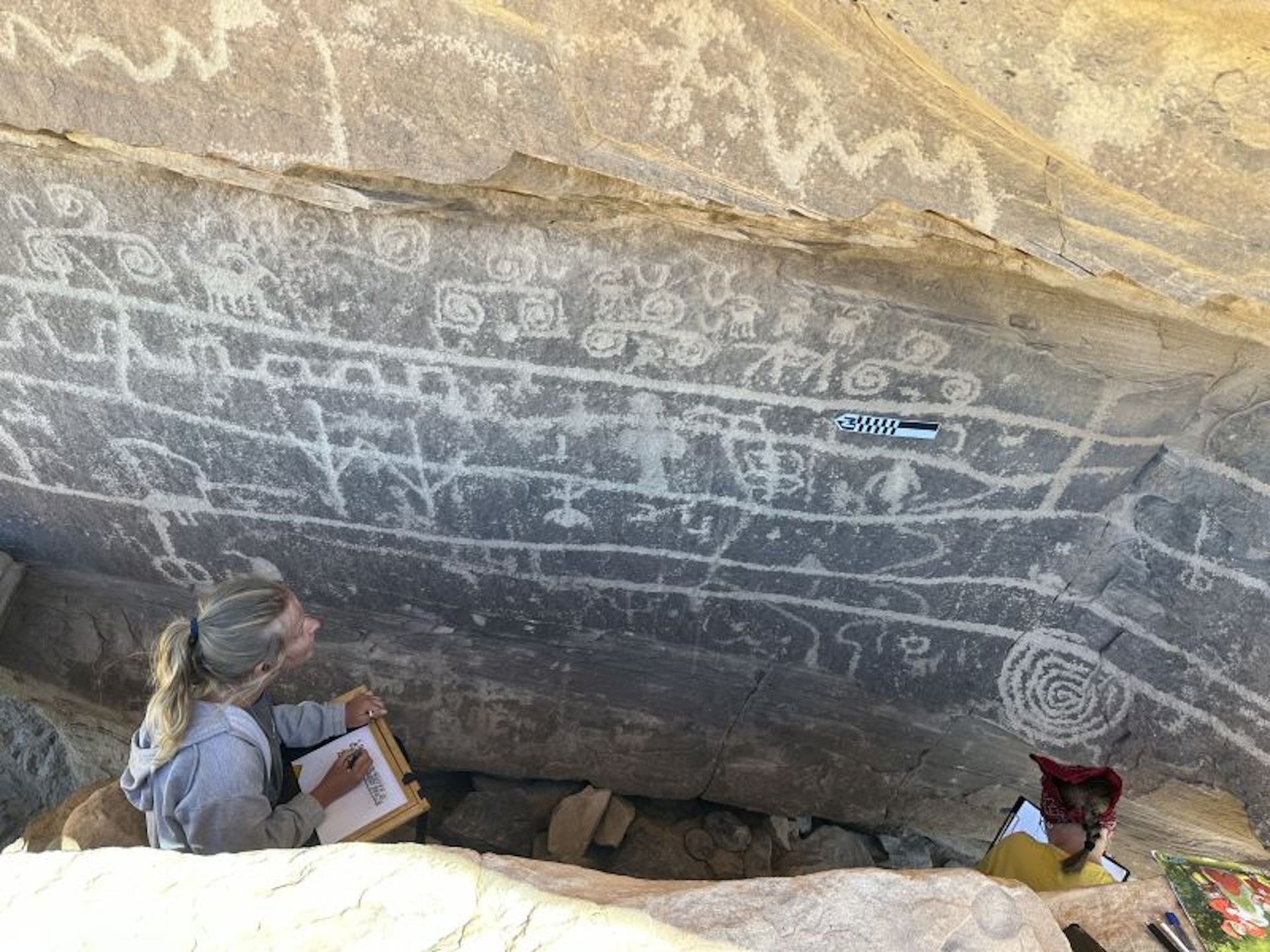

Another ubiquitous feature of Pueblo sites is the rock art of its inhabitants, depicting scenes from everyday life, complex geometry and astronomical subjects. The discoveries of JU archaeologists center around these petroglyphs, carved into ledges previously ignored or considered inaccessible. Among the galleries of rock art discovered are sculptures from the time of the basket makers of the first centuries AD, in which the predecessors of the Pueblo people carved warriors and shamans. Most of the finds, however, come from the height of Pueblo culture in the 13th century, when the large population occupying nearby adobe structures carved shapes and spirals up to a meter in size for suspected religious purposes. Later sculptures of the Ute tribe are also present, depicting narrative scenes of hunting and the post-Columbian introduction of horses to the region.

Researchers examine ancient petroglyphs in Colorado’s Mesa Verde National Park Jagiellonian University

“I had some suggestions from older members of the local community that something else might be found in the higher and less accessible parts of the canyons. We wanted to verify this information and what we found exceeded our wildest expectations. It turned out that about 800 meters above the cliff settlements long ago [of] previously unknown petroglyphs. The massive rock panels stretch more than 4 kilometers around the great plateau,” Palonka said in a statement. “These discoveries forced us to adjust our knowledge about this area. We definitely underestimated the number of inhabitants who lived here in the 13th century and the complexity of their religious practices, which must also have taken place next to these exterior panels.”

Ongoing research at the site will proceed with a two-tiered approach, including collaboration with the University of Houston LiDAR. local team and members of the Ute tribe to produce highly detailed digital maps and intimate historical records of the archaeological site. About the contributions of the Texan scientists, Palonka said he is excited about the prospect of developing “a detailed 3D map of the area with a resolution of 5 cm-10 cm,” a drastic improvement on current images.

With additional help from Ute tribal archaeologist Rebecca Hammond, Palonka’s team will receive help understanding and contextualizing the artifacts they uncover. According to JU, the conversations between the Pueblo people and the archaeologists will be an integral part of an upcoming permanent exhibition at the Canyon of the Ancients Museum and Visitor Center, where the latest discoveries of Polish researchers will also be displayed.

In the meantime, Palonka’s team is eagerly awaiting the results of the new mapping, he said, as they “hope to detect new, previously unknown sites, mainly from earlier periods.”