“War, what is it for? Absolutely nothing!” Motown’s counterculture classic seems particularly relevant as we enter a new year beset by terrible conflict and atrocities. In the face of such relentless warmongering, it may seem perverse to highlight a museum dedicated to the conflict, but I would argue that in these terribly turbulent times the role of London’s Imperial War Museum (IWM) has never been more important.

The First World War was still raging when in 1917 the British government approved a proposal to collect and display material that would record the military and civilian war effort and the sacrifices made by the United Kingdom and its empire. The IWM has since extended its remit to all conflicts involving British or Commonwealth forces, and from its inception, this has included amassing and commissioning a rich and unique collection of art in all media.

The IWM’s collections not only record modern warfare and its impact, but also its aftermath. And this may even include the way in which human conflict changes the parameters of art itself. Surrounded by missiles, tanks and warplanes in the museum courtyard is the twisted form of a wrecked car salvaged from a suicide bombing in Baghdad in 2007. Arranged like a corpse, this grim relic of the Iraq War pierces the bombast of all this lethality . arms and remind us what it really does. The wreck was donated by artist Jeremy Deller after he toured America, accompanied by an American soldier who served in Iraq and an Iraqi citizen living in exile.

One of the most famous works in the IWM collection offers an early commentary on the aftermath of war. Giant painting by John Singer Sargent fizzy (1919) depicts a line of World War I soldiers blindfolded after a gas attack making their way across a devastated landscape, each holding the shoulders of the soldier in front.

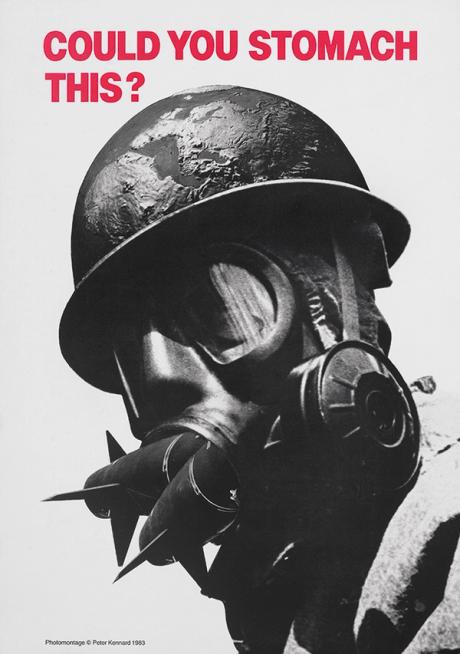

This 6-metre-long work forms the centerpiece of a new set of permanent galleries at IWM designed to house its visual arts holdings and combine art, film and photography for the first time. The Blavatnik galleries opened in November to coincide with Remembrance Sunday, and were organized thematically and not chronologically. There are sections dedicated to Mind and Body; Perspectives and Frontiers; and the Power of the Image, exploring themes of propaganda and protest. This radical re-presentation shows how artists have recorded, commented on and witnessed the wars and conflicts that have shaped our world, as well as underlines how art, for better or worse, shapes what we think and feel about war itself.

Service celebration?

Courageous curation allows powerful conversations to be initiated between works made at very different times. Located directly in front fizzy at Mind and Body Galleries, Steve McQueen Queen and Country (2007) is a memorial to the 160 British soldiers killed in Iraq in the form of sheets of postage stamps, each with a photograph of a deceased soldier, along with their name, age, regiment and date of death. Presented in a special wooden display case with drawers that visitors can pull out, it’s up to us to decide whether Queen and Country it is a celebration of military service or an indictment of loss of life, or both. The Royal Mail refused to issue his designs as official postage stamps, and McQueen considers the work incomplete until it does so.

The myriad of bodily representations range from Henry Moore’s tender 1941 Shelter drawings of Londoners huddled together sleeping in tube stations during the Blitz, to Mohammed Sami’s haunting 2022 painting. Abu Ghraib in the Power of the Image gallery. The latter represents the shape and shadow of a trouser that also recalls the figure of Ali Shallal al-Qaisi, an Iraqi detained and tortured in the Abu Ghraib prison between 2003 and 2004. The images of brutalized bodies are no more powerful than in Edith’s paintings Birkin and Doris Zinkeisen of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp: Zinkeisen was the first artist to enter the camp shortly after liberation in 1945, while Birkin draws on her memories as a survivor of the Bergen-Belsen and Auschwitz camps.

Changing forms of conflict are also charted, from the mass carnage of earlier wars to the more complex, fragmented but no less lethal conflicts of recent years. Representations include Paul Nash’s apocalyptic painting of devastated First World War battlefields to Willie Doherty’s 1995 photograph of a silent charge of a blocked road in Northern Ireland and Mahwish Chishty’s 2013 painted collages and photo transfers which combine the shape of a Reaper Drone with the colors and patterns of Pakistani Folk Art.

In light of recent events, seeing Rosalind Nashashibi’s Electric gauze, filmed in the Gaza Strip in 2014 is almost unbearable. How many of these buildings are still standing? How many of the women who pushed strollers and the children who rode bicycles are now dead? For the sake of those who are currently being attacked everywhere, it is critical that we look long and hard at all of these images and think about what we can each do to stop it all. Now. We hope that one day the IWM galleries will be a reminder of what was, and not a wild reminder of how little we have learned.